|

Rents have risen sharply since 2003 and

deals on view space -- the upper floors of the best buildings -- regularly

topped $60. Vacancy rates at 9.8 percent in the central business

district, and average rents approached $50 a square foot

- May 2007

There are approximately 23 office projects totaling 11 million

sq ft in the

city’s development pipeline, according to a new compilation by the local

office of Jones Lang LaSalle. The total includes 2.4 million sf under

construction; 890,000 sf that are entitled but not yet under construction;

2.67 million sf for which entitlements are being sought; and four projects

totaling four million sf that are in earlier stages of development.

“The city does not publish a list of pending developments,” says JLL’s

San Francisco managing director Chris Roeder. “We did some research

ourselves to try to sort it out and see how the future development is

affected by Proposition M.”

Established in 1986 to control economic growth and development, Prop M caps

the amount of high-rise office development that can be approved for

development at 875,000 sf per development year, which runs October through

September. That means it would take eight years for all of the un-entitled

projects in the development pipeline to be approved for development.

“For probably only the second time since Prop M was passed we are going to

be in a position where developers aren’t going to be able to develop as

much square footage as they would probably like to,” Roeder tells

GlobeSt.com. “The limited amount of future development increases the value

of entitled and un-entitled land. Coupled with high construction costs, I

don’t think we will see any great deals in the next three to five

years.”

The 2.4 million sf under construction is divided among six projects. Two of

those projects--Foundry Square I by Wilson Meany (400 Howard St.; 335,000 sf;

10 stories) and the new Federal Building (1000 Mission; 600,000 sf; 18

stories)--have no availability. A third project, Shorenstein’s 409-411

Illinois St. (five stories; 450,000 sf), is 50% preleased.

No preleasing has been announced for the other three projects that are under

construction. The projects are 555 Mission St. (559,000 sf; 33 stories),

which is being developed by Tishman Speyer and Morgan Stanley; 500 Terry

Francois Blvd. (258,538 sf; six stories), being developed by Lowe

Enterprises; and the 185 Berry St. addition (175,000 sf; two new floors),

which is being developed by Reef.

All of the projects under construction are scheduled for delivery in 2008

except the federal building, which was recently completed. None of the

projects under construction is trying for LEED certification from the US

Green Building Council, according to JLL.

The project entitled but not yet under construction include 330 Bush St. by

Shorenstein (350,000 sf; height TBD); Foundry Square III by Wilson Meany

(505 Howard; 220,000 sf; 10 stories); 524 Howard St. by Higgins Development

and the Pritzker family (275,000; 23 stories); and 44 Fourth St. by

Jamestown Properties (110,000 sf; height TBD).

The largest of the projects currently seeking entitlements are 222 Second

St., a 617,000-sf project for which Tishman Speyer is seeking LEED

certification; 40-90 First St., a 520,000-sf development by Solit Interest

Group; Piers 27-31, a project by Shorenstein and Farallon that tentatively

includes 440,000 sf of office; 1401 Third St., a 420,000-sf project by

Catellus; and 535 Mission St., a 293,750-sf project by Beacon Capital

Partners for which LEED certification is being sought. - 2007

June 22 GLOBE

ST.

Competitive

leases, skilled workers lure Internet, software companies to downtown office

buildings

-2007

Feb 18

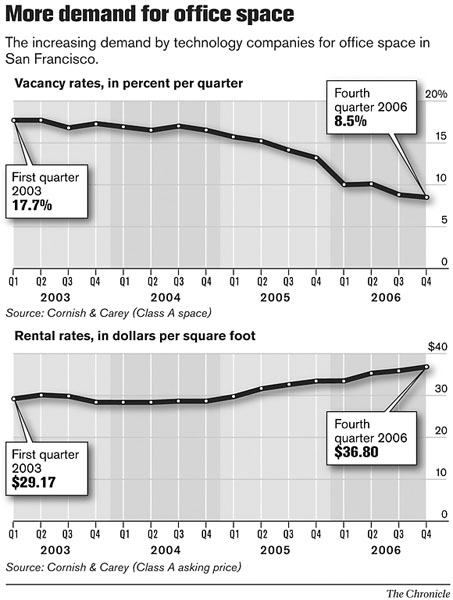

In San Francisco, a quarter of all office space leased in 2006 went to

technology companies, up from 14 percent in 2004, according to the

commercial realty company Grubb & Ellis.

The vacancy rate for Class A space is 8.5 percent, half of what it was

three years ago, according to Cornish & Carey, a commercial realty

group.

The tighter market is driving rents up. The average asking price for

Class A office is $36.80 per square foot, an increase of 30 percent from the

market's trough three years ago.

Still, San Francisco remains competitive. For now, prices remain on par

with Silicon Valley and the East Bay, where the cost of office space is also

appreciating.

Mayor Gavin Newsom said San Francisco has aggressively courted Silicon

Valley companies, calling the jobs they bring a potential boon to the city's

coffers. Each new worker, he said, translates into $1,700 in additional tax

revenue, along with helping local businesses such as dry cleaners, cafes and

markets. "These are the jobs of tomorrow," Newsom said. "They bring

a vibrancy to the city and an excitement, and that's great for us."

- by Verne Kopytoff, Marni Leff Kottle, SAN

FRANCISCO Chronicle 2006 Feb 18

Office obsession

Tech companies are gobbling up office space in San

Francisco. Here are some of the biggest leases, in square feet, since the

start of 2006:

- BEA Systems: 110,000

- Advent Software: 104,000

- Pay by Touch: 92,900

- Microsoft: 71,600

- Riverbed Technology: 63,800

- Yahoo: 42,800

- StubHub: 37,500

- Ingenio: 37,500

Source: SAN

FRANCISCO Chronicle research

EQUITY TRADES:

- Morgan Stanley purchase of 10

buildings from Blackstone - 2007 Feb

24 SAN

FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

- A consortium of private-equity firms offered

$37.6 billion for Equity Office

Properties, topping Blackstone's bid for

America's largest real-estate investment trust. The target of the

biggest-ever leveraged buy-out, Equity Office owns 20m square feet (1.9m

square metres) of office space in Manhattan alone, and is attractive

because rents in many of America's business districts are predicted to

rise. - ECONOMIST

2007 January 23

Billion-dollar office buys rattle

market

The bidding war that ended in Morgan

Stanley's $2.65 billion score of 10 downtown San Francisco properties

suggests there is an enormous pool of international capital looking to grab

a piece of the city's financial district.

From Morgan Stanley to Tishman Speyer to

Broadway Partners, the mightiest minds in international real estate are

placing huge bets on San Francisco that have rewritten the book on what

office space in this city may be worth.

But on a local level, Morgan Stanley's

historic acquisition of the former Equity Office Properties Trust portfolio

from the Blackstone Group has provoked serious questions. Is Morgan Stanley

paying too much? Are tenants willing to pay the $60 or $70 a square foot for

mid-level space that would seem to justify the $675-a-square-foot price that

Morgan Stanley is paying for the 3.9 million square foot portfolio? Will

higher rents drive growing young companies out of the city? Are we heading

toward another office bubble?

A flat world

For the international real estate funds

doing the investing, the argument is global, not local. Dan Fasulo, director

of market analysis for Real Capital Analytics, said the investors are not

comparing San Francisco office values to other U.S. cities, but to markets

across the globe. Average rents in San Francisco are not in the top 50

worldwide and are a fraction of those in London and less than half of the

rates charged in Hong Kong, Dublin, Paris and Moscow. Even Aberdeen,

Scotland, has rates that are 50 percent higher than San Francisco's.

"Investors are now valuing U.S.

office properties with a global perspective, especially in the markets

considered to have the greatest worldwide exposure and business

prospects," said Fasulo. "San Francisco has certainly been

included in this group. If one believes that global office rents will

continue to move towards equilibrium worldwide, then San Francisco looks

very attractive even at the lofty pricing that Morgan Stanley is

paying."

To be sure, Morgan Stanley is getting an

irreplaceable collection of downtown buildings. One Market St., considered

by some to be the most valuable building in the city per square foot, has

bay views even on lower floors. The upper floors of One Maritime Plaza have

some of the best views in the city. The portfolio also includes 405 Howard

St., the Barclay's Global Investors headquarters under construction in

Foundry Square, and 188 Embarcadero, which comes with the parking garage at

75 Howard St., considered one of the best, if not the best, development site

in the city. The Ferry Building was not included in the deal.

But for some who have been around San

Francisco real estate for a long time, the prices feel out of whack. The

$675-per-square-foot price tag is about $75 above replacement costs of new

construction. One executive of a real estate company that looked seriously

at the portfolio said, "the pricing guidance given to us, we couldn't

get comfortable with."

"Obviously there are investors who

are very smart making very large bets," he said. "They could be

right and they could be wrong."

Michael Joseph, a partner at Kearny

Street Capital, suggested that the flurry of investment is being driven by

fund managers who have to allocate a certain amount of capital each year.

"You have to remember that there are

a lot of people within real estate with a lot of money to put out and if

they don't put out that money, they don't get paid," he said. "I

think people who are investing their own money are very skeptical about the

prices being paid."

Empty buildings worth more

February's historic wave of office

building sales in downtown San Francisco was unprecedented in many respects,

but perhaps the most unusual trend is this: High vacancy rates no longer

appear to be a bad thing.

Instead, buyers bullish on future rent

spikes seem to reward the buildings with large blocks of unoccupied space,

even if it means rejecting large deals consistent with today's leasing

rates, which average about $42 a square foot. Buildings like 100 California

St., which is being sold to Broadway Real Estate Partners as part of the

Beacon Capital Partners portfolio, have been intentionally kept empty.

Likewise 333 Bush St., which Prudential is about to put on the market,

according to brokers.

"One third of the financial district

is being priced for sales and not for leasing and therefore it's hard to

make a deal," said Meade Boutwell, a veteran broker with CB Richard

Ellis. "The capital markets are paying more for buildings with vacant

space than they are for leases in place. The big question is, how long are

the legs on this?"

The result is that asking rates jump

dramatically the minute buildings are put on the market. At 333 Bush St.,

asking rates seemingly jumped from $35 to $42 a square foot overnight for

non-view space on the lower floors. At One Market, tenants looking at the

former Accenture space on the 41st and 42nd floors have reportedly been

quoted rents upwards of $100 a square foot, whereas the asking rates were

closer to $80 at the end of 2006.

This has been especially true of the

buildings Morgan Stanley bought, said one broker who asked not to be

identified because his firm does business with Morgan Stanley.

"We've seen a $5- to

$20-a-square-foot jump in the asking rate in the last three weeks," he

said.

Kevin Brennan, an executive vice

president at tenant representative Studley, said the trend should trouble

those who care about the overall health of the city's economy.

"When something generating no return

is more valuable than leased space, that should raise a real red flag,"

said Brennan.

Less demand

At the same time, brokers are seeing less

tenant demand than a year ago, although this is partly because a number of

big firms with 2007 and 2008 lease expirations got their deals done in 2006.

The current requirement of all tenants seeking space is about 2.5 million

square feet, down about 40 percent from a year ago.

Cynthia Kroll, senior regional economist

at the Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics at U.C. Berkeley's

Haas School of Business, said the spike could drive tenants to other markets

and especially hurt nonprofits and foundations, which make up an important

sector of the San Francisco real estate market.

"There will be firms that leave the

city rather than stay, and that could continue the outward flow of firms

that we have seen over the past decade," said Kroll.

In addition to pressures to jack up

rents, tenants will feel the tax increases that come with the sky-high

prices. When the Morgan Stanley deal is complete, the assessed value of One

Market will jump from $300 a square foot to $800 a square foot, and the

burden will be passed through to the tenant. For the typical large law firm

with a 100,000-square-foot existing lease at One Market St., the tax

increase could be $500,000 a year, or $5 a square foot, according to Studley.

"This environment is creating a

tenant crisis, and we're concerned about it," said Steve Barker, also

an executive vice president at Studley.

Patient buyers

Tony Natsis, a partner at Allen Matkins

Leck Gamble Mallory & Natsis who represents top investors like Beacon

Capital Partners, JP Morgan and Boston Properties, said tenants will be

willing to pay the higher rates and all the buyers who picked up pieces of

the EOP portfolio will do fine.

"It's no small wonder that Morgan

Stanley wanted to buy a significant piece of San Francisco," he said.

"It's a great market and you may never get a shot at it again. The

Morgan Stanley guys are going to be very happy."

Natsis stressed that there is a

difference in approach between the REITs like EOP and the international

funds, which have three to 10 years to return a profit to their investors.

Whereas publicly traded REITs like EOP look to boost stock price with high

occupancy rates and low concessions, the new owners can afford to be more

patient. And Natsis said the most active San Francisco investors like

Tishman Speyer, Broadway, Beacon, and Morgan Stanley can afford to buy at a

4 percent capitalization rate, believing that the "cap rates will rise

to 10 percent and beyond in the future."

"There is not a soft guy among

them," said Natsis. "None of those guys are going to give it

away." - 6 March

2007 SAN

FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES

Just two weeks after Blackstone Group

snapped up Equity Office Properties Trust for $39 billion in the largest

leveraged buyout ever, the private equity firm has agreed to sell EOP's San

Francisco portfolio to Morgan Stanley Real Estate for $2.8 billion,

according to industry sources with knowledge of the transaction.

The astounding $700-a-square-foot price

tag for the 4.1 million-square-foot portfolio is more than any single office

building has traded for in San Francisco history. The portfolio includes two

of downtown's premier office towers -- One Maritime Plaza and One Market St.

-- both of which have asking rates well over $70 a square foot. It also

includes some lesser properties such as 60 Spear St.

One

Market Street One

Market Street

The transaction, when complete, will

instantly make Morgan Stanley Real Estate San Francisco's largest landlord.

Other buildings in the portfolio include One Post St. and 580 California St.

The deal is expected to close in 30 to 60

days.

In its winning bid, Morgan Stanley outbid

the REIT Brookfield Properties as well as the privately held Tishman Speyer,

according to sources. Morgan Stanley is also acquiring Equity Office

Properties' Denver portfolio.

In evaluating the San Francisco

portfolio, One Market St. was said to be valued at over $800 a square foot.

A building in San Francisco has never broken the $700 mark. Last summer,

Hines was in contract to sell 560 Mission St. to the Irvine Co. for $700 a

square foot, but the complex deal fell apart after months of negotiations.

The Blackstone buyout has unleashed a $21

billion feeding frenzy of Class A properties across the nation. In addition

to the San Francisco portfolio, San Francisco-based Shorenstein Properties

has already agreed to acquire EOP's Portland, Ore., buildings for $1.1

billion; Maguire Properties has also agreed to pick up 23 buildings in

Southern California for about $3 billion; Macklowe Properties bought

buildings in New York for $7 billion; and Beacon Capital Partners bought

buildings in Washington, D.C., and Seattle for $6 billion.

Since 1991, Morgan Stanley has acquired

$102 billion of real estate worldwide. It currently manages $60.5 billion in

real estate assets on behalf of its clients. -

2007 Feb 23 SAN

FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES

$370 Million Sale| Leaseback - 333 Market

Street - Wells Fargo

2006 Sept 27: Wells

Fargo & Co. has reportedly selected TIAA-CREF to be the buyer of 333

Market, a 620,000-sf Downtown office tower that the bank will lease back on

a long-term, net-lease basis. An industry source tells GlobeSt.com the

agreed upon purchase price is $370 million, or about $596 per sf. The sale

is expected to close before the end of the year. Both Wells Fargo and

TIAA-CREF declined comment.

The sale price is in line with other recent sales of single-tenant

net-leased properties. The Irvine Co. earlier this year paid just over $600

per sf for 560 Mission St., a 665,000-sf Downtown office building net leased

to JP Morgan Chase for the next 11 years. In November, Tishman Speyer Office

Fund paid about $605 per sf for 550 Terry Francois Blvd., a newer 282,733-sf

waterfront office building leased to Gap Inc. through 2017. The length of

Wells Fargo's commitment to 333 Market was not immediately available.

Wells Fargo paid $150 million for 333 Market St. in the first half of 2005,

saying it planned to grow its presence in the building as third-party leases

expire. The publicly held financial services company subsequently invested

an additional $35 million in the 33-story building for a total investment of

just under $300 per sf, a company source told GlobeSt.com in July, when the

property came to market.

The property was marketed by Eastdil Secured, the real estate investment

banking subsidiary of Wells Fargo & Co. The transaction marks the second

significant Downtown purchase for TIAA-CREF in the past nine months.

In December 2005, it acquired Embarcadero Center West from Boston Properties

for approximately $206 million, or $433 per sf. The 475,138-sf class A

multi-tenant office building at 275 Battery St. was about 85% leased,

including a 42,000-sf lease that is scheduled to expire in early 2007.

In June 2005, Wells Fargo paid $110 million, or $323.50 per sf, for 550

California St. and 635 Sacramento St., a two-building 340,000-sf office

complex in the city’s Financial District built in 1960. At the time,

Wells Fargo leased about half the space in the building but, similar to 333

Market, said it would eventually occupy a majority of the building. All

told, Wells Fargo occupies about 2.2 million sf of office space in the city.

- CITY

FEET 2006 Sept 27

Not long after oil prices collapsed in

1986, commercial real-estate markets from Houston to Dallas to Denver

followed suit.

When the tech-stock bubble burst in 2000,

San Francisco seemed destined for the same fate. The city's economy was

reeling, buildings sat empty and buyers disappeared. Just five top-quality

downtown office buildings changed hands from 2001 through 2003.

One of the buyers was Stuart Shiff, whose

firm in 2003 purchased two nearly empty downtown office towers -- once

filled with dot-com tenants -- for $79.5 million.

Two years later, those buildings are on

the market again, for four times what Mr. Shiff paid. More than a dozen

bidders are seriously competing for the deal, brokers say, and banks are

offering liberal financing. Based on prices recently paid for similar

buildings, Mr. Shiff will likely get what he's asking for. "There's

something bubbling here," says Mr. Shiff. "San Francisco is about

to peak."

The city's commercial real-estate market

has made a surprising comeback. Since January 2004, 53 office buildings --

about one-third of downtown's total square footage -- have changed hands,

often for more than they fetched during the tech boom. By contrast,

real-estate markets in cities such as Dallas and Houston were moribund for

years after falling oil prices battered their economies in the 1980s.

San Francisco's rebound says a lot about

investors' current infatuation with real estate and about the vast amount of

available capital flowing around the world. Office rents in San Francisco

are half those in New York -- but investors are paying two-thirds of New

York prices to buy the properties. The problem facing these new buyers:

Charging enough rent to justify the high prices.

Some veteran real-estate executives say

that as in the tech boom, these investors are paying prices that can't be

justified by the market's fundamentals. "San Francisco is improving.

But it just has a ways to go," says Robert Bach, national director of

market analysis for real-estate broker Grubb & Ellis.

Many San Francisco office buildings

remain empty, and the city's vacancy rate is a lofty 16.5%, compared with

8.9% in New York City and 7.1% in Washington. The city's weak job growth

means prospects don't look much better. In the past year, just 8,000 new

jobs were created in San Francisco, Mr. Bach says, while in the strong New

York City market, 57,400 jobs were created, and Washington added 79,400

jobs.

Kevin Brennan, an executive vice

president at commercial real-estate brokerage firm Studley, estimates that

the San Francisco economy will have to create 60,000 new jobs -- including

45,000 white-collar posts -- before demand increases to a point where

landlords can raise the rent. "The buildings that have traded can't

afford to compete with the buildings next door," Mr. Brennan says.

"Any building that sold is going to have a problem."

While Mr. Shiff's firm, Divco West

Properties, had little competition for buildings in 2003, these days new

buyers are appearing at every property sale. In June 2004, when an interest

in an office building at 425 Market St., in the financial district, hit the

market, there were fewer than 10 bidders. The property sold for about $300 a

square foot to Walton Street Capital, according to sales brokers at Jones

Lang LaSalle Inc. When the broker tried to sell a nearby office building in

July 2005, it attracted 30 bidders and sold for nearly $370 a square foot.

Now, Walton Street Capital says it is shopping 425 Market St. again, and

industry officials say the firm is asking as much as $450 a square foot.

In 2004, a group of New York investors

led by Mark Karasick bought the Bank of America Tower at 555 California St.

for $489 a square foot. In September, he sold the building to a group of

Hong Kong investors partnering with developer Donald Trump for $583 a square

foot, for a $171 million profit.

Buyers are finding ready cash from

lenders. Wachovia Corp., a leading commercial lender, has made about $360

million in loans for office properties in the Bay Area this year, compared

with $106 million in 2004.

"Wall Street loves San

Francisco," says Alan Goodkin, a managing director with financial

advisory firm Ackman Ziff, whose business has advised on $689 million in San

Francisco real-estate deals this year, compared with $60 million in deals in

the city in 2004. He echoes the view of many that San Francisco could have a

strong rebound. "You're buying in a market that has been too depressed

for too long," Mr. Ziff says.

San Francisco's comeback has been driven

by a number of factors, including investors' infatuation with hard assets

such as real estate in the wake of the dot-com bust. In addition, landlords

in the city hadn't overloaded on debt, and many were institutional investors

with long time horizons, so there was little panic selling. The tech

companies that went bust had often paid hefty security deposits, which

helped the building owners weather the slowdown. In the late 1990s, space

was so tight that many tech companies signed long leases at bubble-era

rents.

At some points, though, it was unclear

whether San Francisco would suffer the same fate as Dallas and Houston,

which are still struggling to revive their downtowns. Empty office space

flooded into the San Francisco market for three straight years, leaving more

than one-fifth of the city's office buildings empty. Rents tumbled and

unemployment jumped, peaking at 7.5% in the summer of 2003.

But San Francisco has a history of strong

rebounds, helped by its limited land and the Bay Area lifestyle. Those

arguments led Mr. Shiff to buy the two towers, which had served as the

headquarters for oil company Chevron Corp. In 1999, Tishman Speyer

Properties paid $189 million to buy the buildings from the oil company,

which had merged with Texaco in 1999 and moved out of the city. Tishman had

filled the building with dot-com tenants, and after the bust, defaulted on

its loan.

Mr. Shiff and business partner David

Taran started investing in Bay Area real estate in the mid-1990s by buying

10 Silicon Valley office towers. They purchased acres of land in Coyote

Valley in South San Jose, and then cast their eyes on the San Francisco

market following the tech bust, eventually grabbing the Chevron buildings

for $79.5 million from the banks that had taken them back from Tishman

Speyer.

Divco, their firm, tried to lure tenants

with wining, dining and most of all cheap rents. It found its first tenant

in October 2004, when it leased 120,000 square feet to advertising agency

Omnicom Group Inc. Smaller but prestigious tenants such as the James Irvine

Foundation and international document company Océ Business Services also

moved in.

Now, bidders willing to pay high prices

are elbowing out some of San Francisco's most experienced buyers. Investment

firm TIAA-CREF, which has invested in San Francisco real estate for 30

years, was outbid on a half-dozen recent deals by rivals, including foreign

investors, wealthy individuals and other institutional investment funds.

Longtime landlord Douglas Shorenstein,

whose family once owned a quarter of San Francisco's office buildings, is

worried enough about the state of the market that he says he is redirecting

his family's investments toward Boston, Washington and outlying parts of the

Bay Area for better returns. Since 1992, the 50-year-old head of his

family's real-estate fortune has invested more than $3.9 billion in money

from his family and other investors. Mr. Shorenstein describes himself as a

"natural-born worrier." Since 2004, his family has sold five major

San Francisco office buildings. WALL

ST. Journal 2005

Foreign,

institutional investors charging into S.F. office market

San Francisco is an international city and now has

the numbers prove it.

Foreign and institutional cash -- nearly $2

billion in all -- has saturated the office sales market during the past 12

months, tilting the power away from private owners.

During the past year, 54 percent of all buyers in

San Francisco were institutional and foreign, according to LoopNet's most

recent office market report. REITs and other publicly traded entities

accounted for 17 percent of the purchases, while private investors made up

the remaining 29 percent.

On the flip side, just 28 percent of sellers

represented foreign and institutional money, while 45 percent represented

private sellers.

Nationwide, the picture is much different. In the

United States as a whole, just 33 percent of buyers were foreign and

institutional. That number was 38 percent for the West as a whole.

San Francisco also stands out for higher sales

prices ($290 per square foot in the central business district compared with

$247 in the West and $224 nationwide) and increasingly lower returns on

investments.

LoopNet pegs San Francisco cap rates at 6.5

percent in the Central Business District, compared with 8 percent this same

time a year ago. In the West and nationwide, cap rates average 7 percent now

compared with 7.8 percent a year ago.

Market makers are betting properties are still

undervalued from the 2000 crash and big-buck rent increases will continue.

Landlords enjoyed a whopping 20 percent asking-rent increase this past year

-- a number some players expect will slow in 2006, but continue to climb.

Although the average asking rate in the Central

Business District is currently $32 a square foot, according the CAC Group,

landlords of prime space are asking more than double that amount for large

blocks with nice views. - by Lizette Wilson

BIZ

JOURNAL 2005 November 28

Changing spaces :

Recent sales bring new players to S.F. commercial property

At the beginning of 2004, real estate titans

Shorenstein Co. and Equity Office Properties were clearly the dominant

commercial landlords in San Francisco, controlling a combined 11 million

square feet in the city.

Then the selling spree began.

The companies have unloaded nearly 6 million

square feet between them in the last two years, contributing to record

commercial property sales in the central business district and opening the

door to a flood of new building owners.

So far this year, about $2 billion worth of San

Francisco office buildings has changed hands, following $2.7 billion worth

of buildings sold in 2004, according to market research by Grubb &

Ellis.

Today, the new owners include private real estate

funds, pension funds, foreign companies and Pacific Gold Equities, the New

York group headed by syndicators Mark Karasick and David Werner that is

seeking to sell the landmark Bank of America Center only a year after buying

it.

"Real estate is perceived to be a good place

to make money because the alternatives are not as attractive," said

Terry Fancher, who runs Stockbridge Fund, a real estate investment group in

San Mateo that owns China Basin Landing in the city. "People who

allocate capital, whether it's from individuals or pension funds or REITs

(real estate investment trusts), believe they can get a good return on

it."

That's the constant refrain from investors: The

perception of a safe yield and uncertainty about the stock market, not to

mention the low cost of borrowing, are driving real estate acquisitions.

Ironically, the commercial sales frenzy in San

Francisco has occurred despite rents that are at the kind of levels they

were at 20 years ago. At an average of $31 per square foot for Class A

space, commercial rents are nearly two-thirds lower than they were during

the height of the tech boom at the beginning of the decade.

"We've had a divorce between the underlying

market conditions and capital flows," said Dan O'Connor, managing

director of Global Real Analytics in San Francisco. "I'm not saying I

agree with the prices being paid for buildings, but I think there's a bet

being made that the (rental) market will continue to improve.

"This is far from a local phenomenon,"

O'Connor added. "Real estate has been an investment of choice on a

global level."

To some local real estate experts, however, the

gap between rents and building prices in San Francisco is a reminder of the

frothy days of the dot- com stock bubble.

"It really is a dot-commish

environment," said Dan Mihalovich, a tenant broker who runs a Web site

called the Space Place (www.thespaceplace.net).

"An opportunistic owner of the Bank of America building (Pacific Gold

Equities) is trying to flip it for a profit. What more evidence would you

like regarding the speculative nature of acquisitions these days?"

Yet the selling continues with no end in sight.

Indeed, Grubb & Ellis expects to see a new sales record for this year.

Part of the reason, developers say, is that buying

existing office buildings, even partially empty buildings, costs less than

putting up new ones.

The cost of new construction in the city is about

$450 per square foot, far higher than the average San Francisco sales price

last year of $309 per square foot. The BofA complex, by comparison, went for

$444 per square foot last year when it was acquired in phases by Pacific

Gold Equities in a series of highly leveraged deals.

The record in the city is $501 per square foot

paid by a Utah state pension fund for 500 Howard St., one of two buildings

in the Foundry Square development south of the Transbay Terminal.

Apart from the issue of high replacement costs,

many buyers see an upside to the empty space left over from the dot-com

bust. Hines, the city's new top office landlord as measured by square

footage, has just purchased a six- building portfolio from Equity Office

Properties that included two South of Market office buildings with vacancy

rates of 30 and 41 percent.

"The whole strategy is to buy when rents are

low and beginning to increase, so you can benefit from the rise," said

Paul Paradis, Hines senior vice president in San Francisco, in reference to

its SoMa purchases at 301 Howard St. and 405 Howard St., the other building

at Foundry Square. "We don't think we paid a high price because we're

probably in for half of what it costs for a new building. It seems like a

very good deal to us."

Hines hasn't done anything radical to attain the

top spot. The company, which now has 3.41 million square feet of office

space in the city, developed the 101 California high-rise and several other

Financial District buildings in the 1980s and 1990s before switching to an

acquisition mode in the current environment.

But while Shorenstein and Equity Office Properties

have been ferocious net sellers in the last two years -- unloading 4 million

square feet and 1.8 million square feet, respectively, in the city -- Hines

has increased its net holdings in the city by only 260,000 square feet.

This means that while Hines is still in the

acquisition mode, it doesn't have too much exposure to the wide divergence

between buildings' sales prices and rents.

"Nobody really knows how rents will increase

in the next up cycle, and using historical data can be dangerous,"

Paradis said. "But when it picks up, it picks up fast. We have lumpy

cycles in Bay Area real estate. It's not gradual. It's either up or

down."

- By Dan Levy

SAN

FRANCISCO CHRONICLE 2005 Aug 12

Commercial real estate worth more than $2 billion

is on the market in San Francisco, a tenfold increase from a year ago. These

were some of buildings on the block:

| Property |

Owner |

Square Feet |

| 50 Fremont |

Hines-CalPERS |

817,000 |

| 505 Montgomery |

Hines-CalPERS |

346,000 |

| 601 California |

Hines-CalPERS |

251,000 |

| 101 Second |

Cousins-Myers |

387,000 |

| 55 Second |

Cousins-Myers |

374,000 |

| 450 Sansome |

GMAC |

135,000 |

| Hills Plaza |

Shorenstein |

610,000 |

| Pacific Plaza (Daly City) |

Mack-Cali/Summit |

600,000 |

-

Source: Real Capital Analytics; Grubb & Ellis

For

sale in San Francisco

Commercial buildings worth $2 billion are on the block

After four years with virtually no commercial

property sales, San Francisco is suddenly awash in for-sale signs.

Commercial buildings worth more than $2 billion

are on the block, a tenfold increase from a year ago, according to a New

York real estate research firm.

And these aren't strip malls or boutique shops,

either.

The properties for sale in San Francisco include a

half-dozen downtown skyscrapers, comprising about 2 million square feet of

rentable office space.

Among the offerings are three buildings co-owned by developer Hines

Properties and CalPERS, the state employees pension fund, and two South of

Market office towers built and owned by the Cousins-Myers development group.

"Nationwide, investors think rents are going

to be better than they are today," said Bob White, president of Real

Capital Analytics, which tracks large properties. "They see the lower

interest rates going away, and they are more optimistic about the recovery

of the economy."

But some local real estate experts question

whether investors will bite at premium prices -- even with tens of billions

of dollars in pension funds, offshore funds and private equity chasing

commercial real estate.

After all, the skeptics say, average downtown San

Francisco office rents are barely over $30 per square foot -- the same level

as 20 years ago when adjusted for inflation.

Investors typically look for strong rents as the

main justification for plunking down big bucks for a building.

"Some people are placing substantial bets,

but not everyone is jumping on board," said Jeff Congdon of Cushman

& Wakefield in San Francisco. "On the one hand, there is the

feeling that Northern California rents probably won't get worse. But the

question is, when will things start to improve?"

One investor who didn't wait to find out was David

Werner, a Brooklyn investor whose partners have agreed to buy half of the

landmark Bank of America Center for $400 million.

The Werner group paid about $444 per square foot

for the 1.8-million-square-foot complex.

Yet even with white-shoe law firms and investment

bankers in the building, some brokers wonder if Werner group may have paid

too much in the current rental market.

BofA says the building is only 5 percent vacant, but

a recent survey by CB Richard Ellis reported that the building's total

vacancy rate, including sublease space, is closer to 18 percent.

That's not far from the city's overall vacancy

rate of 20 percent. Some experts don't expect that number to be cut in half

until 2009.

"I don't know when those leases roll or what

the current income stream is," Frank Fudem, of BT Commercial, said of

the BofA purchase. "But for a purchase price north of $400 per square

foot, I'd want to take hard look if it was my money."

Still, there is clearly something brewing in the

market nationally.

White, of Real Analytics Capital, said about $40

billion in commercial property came to market nationwide in the second

quarter, "head and shoulders above what we've seen."

The only period that comes close by comparison is

the second half of 2000, when $2.8 billion of commercial property sold just

as the stock market and real estate rent bubbles burst.

Nevertheless, White said, even with the national

office vacancy rate at 18 percent, investors may be willing to take on more

risk in the light of low borrowing costs and an improving economy.

As a testament to the view that investors are

hungry, many San Francisco buildings now on the market do not have asking

prices.

"Sellers are just providing basic financial

information and letting the buyers set the price," said Colin Yasukochi,

research director at Grubb & Ellis in San Francisco. "There's so

much capital and so few quality deals."

Could the current froth be a harbinger of brighter

days for real estate?

White said that San Francisco in the late 1990s

used to be the third-most desirable real estate market for investors, after

New York and Washington.

Then the dot-com bubble burst, jobs disappeared

and the city's allure fell below the likes of Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston

and Miami.

"San Francisco was red-lined for quite a bit,

but it's on radar screens again," White said. "This will be a real

test of investor appetite and belief in San Francisco." -

by Dan Levy SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE 9 July 2004

A new study by the local office of

Newmark has found that class A San Francisco office investments have

performed well for investors over the past decade in spite of the dot com

crash. Newmark’s examination of a decade of pricing statistics for

investment grade office building sales here found that prices increased

overall about 5% while the overall inflation rate (CPI) in the Bay Area

during the same period was 2.9%.

Average prices for high-end office investments in San Francisco rose from

$180 per sf in 1995 to an average of around $325 per sf this year, according

to the study. Of the 35 major office deals closed in San Francisco during

the period, six exceeded $400 per sf.

The study also found that investment-grade real estate prices paid through

the end of 2004 were not the highest prices paid over the decade, as many

might have expected. The Utah State Retirement System-Cottonwood Partner’s

acquisition of 500 Howard Street, a 10-story, 230,000-sf class A Tower

completed in 2003, was the high water mark at about $512 a sf, according to

the study. The largest transaction of the last decade was Boston

Properties’ 1998 acquisition of the 4 million-sf Embarcadero Center for

roughly $1.23 billion, or about $307 per sf.

Private investors, including development and investment firms and high-net

worth families, were the most active buyers over the 10 years. In San

Francisco, however, the office market actually saw a decrease in private

owners as a group, while REITs and institutional investors increased their

market share significantly, according to the report.

The Newmark study concludes that in order to support further price

appreciation or even new development, San Francisco will need to average

Class A rents over $40 per sf with vacancy rates under 10%. Newmark managing

principal Monica Finnegan tells GlobeSt.com that as of the end of June,

direct class A rents in the city averaged around $31 and direct class A

vacancy was 13.7%. Preliminary August numbers show that class A office rents

are up to $33.63 and class A vacancy is down to 13.1%, she says.

“The distance from 13% to 10% is not too great of one, especially when we

see some out-of-market tenants like Yahoo and Google seriously considering

the San Francisco marketplace,” Finnegan tells GlobeSt.com. “With supply

diminishing -- and no real new construction readily on the horizon -- it

doesn't take that much time for landlord's to begin to increase rents,

especially on view or other desirable spaces.” - By Brian

K. Miller GLOBE

ST.com 2005 Sept 5

Office building buying

bonanza continues in San Francisco

San Francisco's sales

streak continued last week with two office buildings closing escrow and at

least three more buildings going under contract.

La Salle Investment Management, working

on behalf of Prudential Property Investment Managers of London, closed

escrow on 201 Mission St. and 580 California St.

The properties, which owner Equity Office

Properties offered along with five others last spring, will be operated as a

joint venture partnership with EOP. La Salle purchased a 75 percent equity

stake in the buildings -- a $163 million investment that gives it control of

796,301 square feet of prime commercial space in the city.

EOP will continue to manage and lease the

buildings.

"The JV arrangement lets us maximize

the investment market and keep the EOP brand out there through the leasing

and management of these two buildings," said Mark Geisreiter, senior

vice president for EOP's San Francisco region, adding he anticipates doing

more business with La Salle in the future: "Our goal is to make these

long-term relationships."

Buyer-seller relationships also matured

on a handful of other properties around the city, according to sources

familiar with each of the arrangements:

Beacon Capital Partners placed 100

California St. under contract from Westbrook Partners for roughly $360 a

square foot.

Lowe Enterprises, which also manages the

Transamerica Pyramid, has placed 300 California St. under contract for an

estimated $33 million, or $269 a square foot. ATC Partners is the owner.

San Mateo-based Glenborough has placed 33

New Montgomery St. under contract for an estimated $70 million, or $291 a

square foot. Blackstone/McCarthy Cook is the owner.

Grubb & Ellis' researcher Colin

Yasukochi, who tracks investment sales, said the continuing high activity

and high prices don't surprise him.

"Those prices are consistent with

the market, but still well below replacement cost," he said, noting the

cost to build anew is $525 a square foot in construction and land -- well

above last year's $425 a-square-foot mark.

"In today's market you have to

be aggressive with the pricing to win the deal. Whether the buyers can

achieve the rents they expect to and have built into the pricing will

determine whether the purchase price was correct or not." -

BIZJOURNALS

2005 July 25

Wells

Fargo Picks Up 340,000 SF for $110M

Wells Fargo Bank N.A. has paid $110

million for 550 California St. and 635 Sacramento St., a two-building office

complex in the city's Financial District built in 1960. The price for the

340,000-sf property is about $323.50 per sf, which is about average for 2005

class A sales in the city. The seller, SPI Holdings, acquired the building

in 2001 for $106 million.

According to local sources, Wells Fargo leases about half the space in the

complex, which is located within one block of its headquarters at 420

Montgomery St. The bank’s consumer credit, creative services, capital

markets, strategy and finance, and the corporate banking departments occupy

space in the buildings. Wells Fargo says it will eventually occupy a

majority of the buidling

None of the parties involved in the transaction returned phone calls seeking

comment. According to published reports, the 550 California site in the late

1800s was a paddock for horses that pulled Wells Fargo stagecoaches.

Earlier this year, Wells Fargo acquired 333 Market St., a 620,000-sf

building that Wells leases space in for some of its back-office operations.

Wells Fargo says it will ultimately occupy a majority of the building. Local

industry sources tell GlobeSt.com that the purchase price was $150 million

or $252 per sf.

All told, Wells Fargo occupies about 2.2 million sf of office space in the

city. - 9 June 2005

GLOBE

ST

Foreigners Seem To Be Souring On

U.S. Assets

At a time when U.S. trade deficits are growing to historic

proportions, foreign interest in U.S. stocks and bonds may be fading. If

this continues, there could be consequences for U.S. interest rates and the

dollar.

Foreign purchases of securities in

the U.S. in May came to $56.4 billion. While that was large enough to

finance the current-account deficit, it was down 26% from April and

represented the lowest monthly total in seven months. It also marked the

fourth consecutive monthly decline of such purchases by foreigners.

The report on foreign purchases

included bad news for U.S. stocks, revealing that May was the third

consecutive month foreigners have been net sellers. That hadn't happened in

nearly a decade.

Potentially more troubling was the

slowdown in Asian purchases of U.S. debt -- especially in Japan, which holds

16% of all U.S. Treasurys. That country's nascent economic recovery has

eased the government's concerns about maintaining a weak currency to boost

exports, in turn reducing the Bank of Japan's need to intervene and buy

dollars.

The result: Japan bought $14.6

billion in U.S. Treasurys in May and $5.5 billion in April, according to the

U.S. Treasury Department. That is a significant drop from a monthly average

of $25 billion for the seven-month period ending in March. If the Japanese

economy continues to rebound, Tokyo's Treasury purchases are unlikely to

return to those lofty levels. That has some economists concerned.

"Japan is to the U.S. financial

markets what Saudi Arabia is to the world oil markets -- the primary

provider of capital," Joseph Quinlan, chief market strategist for Banc

of America Capital Management, wrote in a recent report.

"Self-sustained growth in Japan could ultimately obviate the need for

the Bank of Japan to purchase U.S. securities, leaving a buying void in the

U.S. Treasury market, helping to drive yields higher." Bond prices and

yields move in opposite directions.

Indeed, in the two months that

Japanese buying of Treasurys slipped, the yield on the 10-year note jumped

to 4.65% at the end of May from 3.88% on April 1, though it has since fallen

to 4.43%.

The Bank of Japan and other Asian

central banks have become an increasingly important pillar of support for

the Treasury market, because their currency interventions and large trade

surpluses with the U.S. have resulted in excess dollars to invest. Since

these central banks are concerned less about a high rate of return than a

stable and easily tradable investment, U.S. Treasury debt has been a major

beneficiary.

Yet if recent trends toward lower

U.S. investment persist, the U.S. eventually could have a tougher time

funding its current-account deficit, which reached a record $144.9 billion

in the first quarter. Any trouble financing that deficit would lead to

higher borrowing costs through rising U.S. interest rates. It also could

cause the dollar, which hit a three-week high against the euro on Friday, to

resume its decline.

Indeed, problems with the current

account could end up making the dollar "possibly quite a bit

weaker," said John Llwellyn, chief global economist for Lehman

Brothers.

For now, however, funding the

current account shouldn't be a concern, said Rebecca McCaughrin, an

economist for Morgan Stanley. She noted that in 2004 the U.S. needs to

attract a monthly average of $50 billion to fund that deficit. After

averaging $82 billion for the first four months of the year, the U.S. need

attract only about $35 billion a month for the rest of the year.

"Europeans alone could do it," Ms. McCaughrin said.

Still, foreigners now control 40% of

U.S. Treasury debt, and their purchases are unlikely to return to peak

levels seen at the start of the year, she said. "So U.S. interest rates

could still go higher, even if the current account is funded," Ms.

McCaughrin said.

Other foreign investors' appetites

for U.S. securities also have been waning, in part because rising oil prices

have forced some countries to spend more of their dollar reserves on energy.

That leaves fewer dollars to invest in the U.S. markets.

Mr. Quinlan said that is the case

for China, Asia's second-biggest buyer of U.S. securities, which bought $13

billion in U.S. assets through May, compared with $33.1 billion a year

earlier.

The pullback in Beijing's interest

in U.S. Treasurys was larger still: China was a net purchaser of $1.7

billion of U.S. Treasurys in the first five months of the year -- down 91%

from the $18.4 billion in net purchases a year earlier.

Even the United Kingdom, long a

reliable buyer of U.S. securities, turned negative in May, with net sales of

$4 billion. That was its first monthly net sale since October 1998 during

the near collapse of giant U.S. hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management and

the aftermath of the Russia financial crisis. Clear hints from the U.S.

Federal Reserve that it would be raising interest rates likely caused U.K.

investors to trim positions in U.S. Treasurys, Mr. Quinlan said.

Anticipation of the Fed's first rate increase in four years also may have

contributed to the three consecutive months that foreigners sold U.S.

stocks.

By many accounts, however, Japan

remains the critical buyer. Mr. Quinlan argued that Japan has become

"America's de facto banker, helping to keep U.S. interest rates low

over the past year." Currency traders say the Bank of Japan hasn't

intervened in the currency market since March, and the pace of Japanese

Treasury buying of the recent past looks unsustainable: Japan bought $175

billion in U.S. Treasury debt from September to March, a figure that exceeds

Japanese purchases of Treasurys in the previous seven years combined.

Ms. McCaughrin said there has been

anecdotal evidence that private Japanese investors, including banks and

pension funds, also have been scaling back purchases of U.S. assets and have

been investing more locally, to take advantage of a rebounding Japanese

economy, or in other overseas markets, to capitalize on the global economic

expansion. - by Craig Karmin WALL

ST JOURNAL 2004 July 26

OLD NEWS:

Hines purchased

with Calpers the 42 storey Fifty Fremont Center comprising 795,000 sq ft

from Bechtel and Shorenstein Company. The project was

constructed in 1983 and is 100% occupied with tenants including Deloitte

& Touche, Pillsbury and Merrill Lynch.

Calpers has also expanded to become the US' largest landlord of

neighbourhood shopping centre with its $800 million acquisition of 63

centers in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest.

Office condos trend picks up steam

(~$525 psf)

2996 March 3:

The next wave of downtown condo conversions may be more about

cubicles and conference rooms than master bedrooms and sub-zero refrigerators.

The classic Beaux Arts Medico-Dental building at

490 Post St., on the edge of Union Square, is about to be converted into

commercial condominiums, joining the Adam Grant Building at 114 Sansome St.

as downtown buildings entering the office condo market. While newly

constructed commercial condo developments have taken off in suburban

markets, the two projects mark the first historic downtown San Francisco

office buildings in nearly two decades to be sliced into individual units

and sold off to business owners.

And developers of both projects are betting the

payoff will be rich and could inspire other conversions.

Developer John Sikora bought 490 Post St. for $44

million in February 2005 with two Sacramento-based partners. He expects the

building to fetch more than $70 million, with commercial suites selling for

an average of $525 a square foot. The 130-unit building, which is 88 percent

occupied, is predominently used for small medical offices. Sikora said he

has not started marketing the building, but interested doctors and dentists

are already lining up.

"There are 130 tenants who come in here to

work every day," Sikora said. "That is a pretty captive

audience."

The 114 Sansome building was snapped up for $49

million, or $275 a square foot, by Bayview Sansome Street LLC, a subsidiary

of Miami-based Bayview Financial. Grubb & Ellis, who is

representing the new owner, estimates individual office suites in the

14-story, 189,000-square-foot renovated building will fetch between $400 and

$500 a square foot. He expects the building, once fully sold, will generate

$75 million.

Attorney and real estate broker Michael Schroeder,

who is representing several tenants in the Post Street building, said his

clients are generally receptive.

"Once this happens, there are going to be

other owners that will be converting to condos," said Schroeder.

"I think it's a sign of the times."

Dumas said the two buildings are not competing for

the same type of buyer. While 490 Post St. is nearly all medical, the

Sansome Street building is tailored for accountants, lawyers, architects and

non waste-producing medical uses. The building is 50 percent occupied.

Roughly 25 percent of the tenants have leases that expire by the end of the

year. While he is just beginning to market the property, Dumas has letters

of intent with three current tenants: a medical user, a public relations

firm and an accounting office.

Sikora said his project was partially inspired by

the success of the Mill Valley-based Venture Corp., which has completed 34

newly constructed commercial condo projects across the Western United

States.

Venture Corp. President Robert Eves said a

combination of low interest rates and the tax advantages of ownership are fuelling

the trend. While most condo conversions have been done in suburban markets,

he said the concept could translate to San Francisco, but only in especially

attractive, well-appointed buildings. He said a developer in the late 1980s

attempted to convert the Humboldt Bank Building at 785 Market St., but the

deal flopped.

"We would be very fussy about any property in

San Francisco," he said. "There is a significantly different

mentality between the person who wishes to rent and the person who wishes to

own."

Dumas agreed that the building is important. It

has to be well located and in good condition. He said buildings that were

"blown out" during the dot-com era to accommodate larger tenants

are not as attractive for office condo conversion because most office condo

tenants are in the market for 1,000 to 5,000 square feet.

Still, he thinks there are plenty of candidates in

San Francisco.

"I think a year from now we'll look back and

there will be a half dozen to a dozen buildings in the city that have

converted," said Dumas.

Eves said he does not see the office condo trend

slowing down.

"We developers are sheeps," he said.

"Somebody has a clever idea and we all follow." - San

Francisco Business Times 2006 March

|