|

Digital TV penetration (%)

| Country |

2005 |

2009 |

2015 |

| Australia |

30% |

68% |

100% |

| China |

1% |

17% |

54% |

| Hong Kong |

58% |

87% |

100% |

| India |

5% |

21% |

52% |

| Indonesia |

1% |

2% |

14% |

| Japan |

34% |

47% |

82% |

| Malaysia |

40% |

60% |

79% |

| New Zealand |

34% |

65% |

100% |

| Philippines |

1% |

5% |

21% |

| Singapore |

19% |

69% |

100% |

| South Korea |

14% |

44% |

83% |

| Taiwan |

6% |

16% |

70% |

| Thailand |

2% |

12% |

27% |

| Vietnam |

1% |

12% |

57% |

| Asia Pacific

Region |

6% |

21% |

54% |

Source: Informa

Telecoms & Media

-

Asian

Moms hooked on the Internet

-

Asians

are World's Most Engaged Net Users (2008

Dec)

-

China's online advertising market

grew 21.2% in 2009 to $3.02 billion. That spending was split among search

engines, online video, virtual communities and traditional internet portals.

Events such as the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, the Asian Games in Guangzhou

and the FIFA World Cup, are expected to boost online ad revenue above $4.4

billion in 2010. Source: iResearch Consulting Group

AD AGE CHINA

ONLINE SHOPPING

More people in the region are shopping

online, a survey has found. And Singaporeans are no exception.

The Visa survey shows shows that Internet

users here were the second-highest spenders online in the region in the past 12

months. Only Australians spent more. And with more online shopping, credit card

companies are gaining, with Visa leading the way. According to the survey,

almost 60 per cent of online shoppers used Visa to pay.

The survey also looked at the top three

reasons why people in the region buy online. Eighty-eight per cent said that

online prices are cheaper. And 82 per cent said that it is easier to shop online

than conventionally.

Online shopping is most popular in certain

categories - digital entertainment, followed by travel and fashion. Most money

spent online in the region is for travel. The average among travel spenders in

the survey was US$812 in the past 12 months. Mohamad Hafidz of Visa Asia-Pacific

said: 'Almost a quarter of the world's population - roughly 1.4 billion people -

used the Internet on a regular basis in 2008. And in the Asia-Pacific, on

average a person spent about 20.2 hours a month online.

'Our survey has revealed that online

consumers in the Asia-Pacific recognise the convenience of online shopping, as

reflected in the high percentage of Internet users who buy a wide range of

products from those for everyday use to the occasional high-value item.'

The Visa e-Commerce Tracking Survey was

conducted by Ipsos, with respondents from Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Korea,

Australia and India. - 2008

November 21 BUSINESS TIMES

Slump May Help China's Online-Ad Market

Online advertising, which has gained traction in China in recent years,

may be one of the few sectors to benefit from the country's sharp economic

slowdown, as companies here look for more cost-effective ways to plug their

products.

Ad-industry executives and analysts say the need to trim costs, while

still trying to woo customers, could cause the online, or digital, portions

of companies' ad budgets to grow, giving a boost to a market that has grown

rapidly but remains puny compared with its size in the U.S.

"The economic crisis is...prompting a lot of our clients to rethink

their marketing spending," says Karl Cluck, a Shanghai partner at

Mindshare, a media-buying unit of WPP PLC, which has worked with clients

including Nike

Inc. and Motorola

Inc. in China. There is "a lot more interest" in digital

advertising, he says, especially for marketers of youth-oriented products.

China already boasts the world's largest population of Internet users,

not to mention the most mobile-phone subscribers. But companies in China

allocate 5% or less of their ad budgets to the Internet, depending on the

estimate, compared with more than twice that share for companies in the U.S.

That has been changing, as young Chinese consumers gain more market clout

and companies become more comfortable with the Internet in China. Nielsen

Co. estimates that online ad revenue in China in the third quarter grew 42%

from a year earlier to 3.72 billion yuan ($541 million). That rate was more

than double the growth in spending on television, newspaper or magazine

advertising.

Online video sites like Youku.com and Tudou.com are getting big

advertising clients, including Samsung Electronics Co., Mazda

Motor Corp. and Nike's Converse Inc. Marketing collaborations between

brands and Chinese Web platforms also are becoming more common.

Last month, Coca-Cola

Co. did an Internet campaign for its Coke Zero line, asking users of

Xiaonei.com, a social-networking site owned by Beijing-based Oak Pacific

Interactive, to submit photos to show why they deserved to be the next James

Bond. Winners received a "day of James Bond," including a ride in

a helicopter and an Aston Martin sports car.

The near-term outlook for online ads in China isn't entirely positive.

Big advertisers in the auto and real-estate sectors are already feeling the

effects of the slowing economy, and if overall spending falls sharply,

online media will feel a hit.

Jason Brueschke, a Citigroup analyst in Hong Kong who covers China's

Internet market, says the impact of China's slowing growth over the next

three quarters may be greater than people realize. Even if marketing budgets

being drawn up now are strong, "it doesn't mean the budgets will

actually get spent," he says.

In a deep downturn, Mr. Brueschke says, marketers will need to choose the

most valuable advertising, which is still television. Indeed, China Central

Television, the monopoly state broadcaster, last month took in $1.4 billion

for 2009 in its annual auction of prime-time commercial spots, a

year-to-year increase of 15%.

Shaun Rein, founder of Shanghai-based consulting firm China Market

Research, sees the CCTV auction as a positive sign of advertiser sentiment.

The auction shows "ad prices are still going up in China," he

says. "With most companies that we've worked with in China, they're

keeping their marketing budgets kind of stable," but looking for ways

to get more bang for their ad dollars through channels like the Internet.

Mr. Cluck projects that the Internet's share of some companies' ad

budgets in China could increase by a percentage point over the next year.

"That's where customers are going to be," he says. That means that

even if the overall ad pie shrinks, Internet media will have a greater share

of the total, and be well-positioned for any rebound.

Citigroup's Mr. Brueschke says money being spent for online advertising

will more likely be allocated to bigger established Internet companies like Sohu.com

Inc. or Sina

Corp., rather than edgier sites like the video-sharing Web sites that have

gained popularity in recent years. This happened during the Olympics; after

the Games, China's top two Web portals posted much stronger growth while

other large Chinese Internet companies, including Tencent

Holdings Ltd. and Netease.com

Inc., underperformed relative to expectations.

Despite his concerns about the near-term outlook for China, Mr. Brueschke

thinks China is in a better situation than many ad markets. When advertisers

make world-wide ad-budget decisions, China looks "a whole lot better

than Europe and the U.S.," he says. "If you're playing the China

market, you're playing the long-term, not the short-term, game," Mr.

Brueschke says.

- 2008 December 11 WALL

ST JOURNAL

Although many of the Internet's basic infrastructure grew

out of U.S. government and academic research in the 1960s and 1970s, most

Internet users are now outside the United States. The computer network has grown

into a critical international tool for communications and commerce.

Who would have imagined the

impact of Internet technology just a few years ago? Asians have really

embraced the technology. We saved a few articles from as early

as Dotcom 1.0 era which illustrate

the point.

China says its population of Net users now

world's No1

China's fast-growing population of Internet

users has surpassed the United States to become the world's biggest, with 253

million people online at the end of June, the government reported yesterday.

China's Web usage is growing at explosive

rates despite government efforts to block access to sites deemed subversive or

pornographic. The financial size of China's online market, though, still trails

those of the US, South Korea and other countries.

The latest figure on Internet users is a 56

per cent increase from a year ago, the China Internet Network Information Center

said.

'This is the first time the number has

drastically surpassed the United States, becoming the world's No 1,' a CNNIC

statement said.

The United States had an estimated 223.1

million Internet users in June, according to Nielsen Online, a research firm.

China's Internet penetration is still low at

just 19.1 per cent, leaving more room for rapid growth, according to CNNIC. The

Pew Internet and American Life Project places US online penetration at 71 per

cent. - 2008 July 26 AP

A definitive article by Morgan

Stanley analyst Mary Meeker published in 2004 outlined in a 200+ page

report on Internet use in China, the world's second-biggest online market.

``This is the report we wish we had been able to read

before we began to dig into the market for the Internet in China,'' the report

says. ``We have been intrigued by the potential in China for more than half a

dozen years, but did not think the time was right for a big ramp in focus until

the middle of last year.''

China's online community increased to about 87 million

in June this year and JP Morgan is forecasting it will reach 138 million by

2006.

China had 79.5 million Internet surfers in 2003, a

year-on-year increase of 34.5 per cent, the China Internet Network Information

Centre (CNNIC) in Beijing said.

This puts the mainland comfortably ahead of Japan's 56

million users, but still at number two behind the US, which had 165.75 million

users, the Central Intelligence Agency said in its World Factbook. China defines

an Internet user as someone who accesses the Internet at least one hour per

week. The CNNIC added that dial-up Internet access from the home accounted for

about 45 per cent of China's Internet use while almost 25 per cent came from

leased lines and about 10 per cent via broadband connections.

The number of computers with access to the Internet

grew by 48.3 per cent to 30.89 million by the end of last year.

All this means strong earnings impetus, especially for

the big three Nasdaq-listed Chinese portals, which have seen their respective

share prices soar to record highs.

Sina.com hit US$49.50 (HK$386) on January 27 of this

year, less than 12 months after its share price hovered just above US$5.

Similarly, NetEase.com and Sohu.com both experienced a sixfold jump in their

share prices in 2003 alone, having emerged from a two-year slump that followed

the dotcom bust. Share prices have since settled back to mid-2003 levels.

``In my view, the China Internet sector still presents

an exciting growth opportunity over the long term. I don't see a bubble when

stocks are trading at their 52-week lows and at multiples similar to traditional

media or entertainment software levels,'' Lehman Brothers analyst Lu Sun said.

The rocketing trend of online activity in China has

not gone unnoticed among foreign giants of the industry.

Within the last year, eBay, Google, Yahoo and

InterActiveCorp along with some mainland competitors have invested almost US$1

billion in Internet businesses.

Ctrip.com International, a Shanghai-based online booking

agency for hotels and airlines in China, raised US$84.6 million (HK$659.9

million) in December by issuing American Depositary Receipts on Nasdaq.

In June, Japanese online shopping mall operator

Rakuten paid US$110 million for a 21.61 per cent stake in Ctrip.com which

reported second-quarter net income of 31.44 million yuan (HK$29.6 million ) and

now has a market capitalisation of roughly US$500 million.

In Hong Kong, JobsDB.com, an online provider of

recruitment services, formed a strategic alliance with Shenzhen-based

chinajobonline.com to tap the mainland labour market.

According to JobsDB.com chairman and CEO Samuel Sung,

who co-founded the company in September 1998, chinajobonline.com operates on a

membership scheme with annual fees typically between HK$2,000 to HK$3,000 for

postings within China.

JobsDB.com's Hong Kong per posting fees can be more

than HK$900. Cross-border postings on the two websites, launched in 2002, cost

extra.

``China is a proven market for Internet companies in

terms of making real money versus future earnings,'' an analyst with a US

investment bank said.

For the three Chinese portals, messaging services have

been key to driving revenues although NetEase.com is deriving a bigger chunk of

sales from online games, an area Sina.com and Sohu.com are playing catch up.

Advertising, which accounted for half of NetEase.com's

revenue in 2001, was just 16 per cent in fourth quarter.

For Sina.com and Sohu.com, online advertising drives

about 40 per cent or 50 per cent of their total revenue ``and that's still the

most important and strategic part of their businesses'', Lehman's Sun said.

While adopting this three-pronged business model to

diversify their revenue streams produced profits in the aftermath of the dotcom

bust, Morgan Stanley's Meeker noted: ``If the Internet leaders can sustain solid

revenue growth in messaging, advertising, gaming and other new initiatives in

2004, they should be well established for subsequent years.''

CNNIC surveys of Internet surfers last year found that

only 8 per cent have never visited a shopping website, while 40 per cent have

made online purchases, including books and audiovisual and communication

products. They also average almost 11 messages each per week, while gamers spend

about 11.3 hours each week online.

In 2003, the state General Administration of Press and

Publication approved 37 online games.

JPMorgan, which initiated coverage of the Chinese

Internet sector in May, estimates the market will pull in US$190 million in

online advertising this year, US$1.03 billion for wireless value-added services

like messaging and US$439 million for online games.

These full-year forecasts represent year-on-year

growth of 60 per cent.

Online search, online auctions and e-commerce are also

dotcom business models that JPMorgan expects will develop into important revenue

drivers.

Principal analyst Marcus Sigurdsson, at leading IT

industry analysts Gartner, describes the mainland Internet market as developing

into ``a content ecosystem or value chain, where there is a customer base that

wants content and companies that produce content for delivery''.

This is driven, in part, by China-specific online

behaviour that is turning the Internet into a socialising tool and a key source

of entertainment and information, JPMorgan said. ``Young people in China

consider getting an entertainment activity online. Online games are very popular

in the country and the market is expected to see double-digit growth in 2004,''

it said, pointing out that hourly fees charged by Internet cafes are between two

and four yuan.

Writing in the Asia newsletter of Boston-based

investment services company Asia Clipper, William Hui Rong points to two key

factors for this growth in China's online gaming industry.

``First, online games are piracy-free compared with

traditional personal computer games. A person can copy a PC game by installing

it on his own computer but he can't do the same to online games.

Online games require each player to pay to get a

unique ID to play online, a process which cannot be easily pirated.

``Secondly, online games provide much richer

interactivities with other players than traditional PC and video games.

``The hottest genre is MMORPG [Massive Multiplayer

Online Role Playing Game], where players compete or cooperate with each other,

meaning that the real fun comes from real person interactions.

``By comparison, in traditional PC or video games,

players follow predesigned plots that have only limited possible outcomes and

become boring after some time.''

But there are also risks of state interference in any

media business in China. Just last month, state-owned China Mobile suspended the

important mobile messaging business of Sohu.com for one year for sending out

text messages promoting its picture messaging service to China Mobile customers

without approval.

China Mobile also fined Sohu.com about US$500,000

The penalties sent the shares of Sohu and other

US-listed Chinese internet stocks tumbling as investors reacted negatively to

the reminder of Beijing's overall control.

The penalties were widely condemned by wireless

service providers as being too harsh but it did serve to expose the volatility

of wireless revenues.

``We believe for the next two months or so, until

October at least, these activities will continue, with various levels of fines

and sanctions applied against smaller players and possibly a few larger ones.

``The reason for the continuation of this process is

that the pressure, in our opinion, comes from the Ministry of Information

Industry (MII) and not China Mobile.

``This pressure will continue until China Mobile

officials convince MII that all the content has been cleaned and no aggressive

marketing or billing practices are used anymore.

``There is a limit, of course, in how much MII can

push this since we believe too much pressure will backfire with China Mobile

complaining that MII is killing the market opportunity and hurting all the

players,'' a Piper Jaffray & Company research report said, warning that the

third quarter of this year will be the worst for wireless service providers.

State regulation has also expanded to include review

of the content of online games before being installed and operated by Internet

cafes. This stems from Beijing's recent crackdown on pornographic material.

A licence from China's Ministry of Culture is required

to host live game competitions and related marketing events.

``This trend has been the major theme in the entire

history of Chinese media, and new technology platforms like Internet portals and

wireless protocols were not under such tension since they were quite small

compared to other traditional media during the past years,'' Piper Jaffray

added.

The two parties that would likely be affected by this

increased scrutiny are NetEase.com and Nasdaq-listed Shanda Interactive

Entertainment. According to Morgan Stanley, NetEase.com's most popular online

game is Westward Journey Fantasy. Launched in January this year, the game was

developed in-house, which means the company does not have to split revenues with

game developers.

Shanda has also had its share of problems with Korean

game developer Wemade over accusations Shanda copied content from the licensed

Legend of Mir series for its first in-house developed title, World of Legend.

Shanda hosts the popular Legend games in China for

paying members who fork over 35 yuan for 120 hours of playing time.

In 2003, this translated to revenue of US$72 million

and net profit of US$28 million.

Considering that more than 40 per cent of China's

Internet users have monthly incomes of over 1,000 yuan, this is impressive.

Many naysayers wrote off the Internet as a money-maker

following the Nasdaq crash of 2000.

But just 35 years after UCLA professor Len Kleinrock

and a team of graduate students gave birth to the Internet by transmitting data

between two computers on September 2, 1969, China is clearly demonstrating that

the medium can make money.-

HONG

KONG STANDARD 4 Sept 2004

Asian data traffic set to jump 35-fold in

next four years

In the next four years, Internet traffic

within Asia is set to grow 35-fold, while data traffic between Asia and North

America will only go up six or 10-fold. Asian telcos and submarine cable

providers should capitalise on this and make money for their stakeholders.

That's the prognosis from Tokyo-based

Tsunekazu Matsudaira, CEO of submarine cable operator C2C Pte Ltd, a subsidiary

of Singapore Telecommunications Ltd. 'Analysts we talk to say that between now

and 2006, intra-Asia Internet traffic will grow 35 times,' Mr Matsudaira told

BizIT in an interview. 'It is set to grow only five-fold within the US during

this period. True, submarine cable capacity may be a commodity business. But

money can still be made from it if the business case is well made.'

He said Asian telcos are still at the early

stages. 'However, all the market studies we see - we're commissioning another

one soon - have shown there will be robust growth of 40 per cent a year over the

next 10 years in both data and voice, but obviously more for data.'

So far, the dominant destination of Internet

traffic from Asia was to the US. That led to a significant overcapacity on the

trans-Atlantic route. But the same is not true of the intra-Asia data routes.

For instance, the Japan-US link, which is now the most heavily used part of the

trans-Pacific submarine cable network, has 25 times more data traffic than

voice.

Hoh Wing Chee, C2C's COO, said: 'When Asian

carriers have to pump Internet traffic to the US, they do not just pay the

wholesale costs (for bandwidth), they also pay international leased circuit

costs (which the carrier pays to his counterpart in the call destination). These

expenses have prodded Asian carriers to network among themselves so they can

send traffic to each other.'

Mr Hoh said that cable overcapacity showed

variations between Asian destinations. Much of the planned capacity did not

materialise because the operator ran into financial difficulties. Another

reason: technological innovation. This was a key factor contributing to initial

submarine overcapacity. For example, almost all submarine cable that was laid in

the Asia-Pacific region since 2001 used DWDM (dense wave digital multiplexing)

technology. This technology offers up to 100 channels over each optical fibre

pair, a 3,500-fold increase over the previous generation of trans-ocean cables

that were used 15 years ago.

'The spurt of intense innovation gave cable

operators much more capacity at the same price,' Mr Matsudaira said. 'The cable

operators thus rushed in to build capacity well in advance of demand.' That in

turn drove down the already-low prices for data transfer.

'But the trick is deciding when to 'light'

(an industry term that refers to turning on or using the unused capacity) in the

optical fibre', he said. 'Clearly, prices will fall as capacity expands. But the

pace depends on how well we plan our rollout. As the number of players decreases

and the industry consolidates, we will see signs of prices stabilising.'

C2C laid the submarine cable after the

bursting of the cable bubble in 2001. That collapse saw prices for IRUs

(indefeasible rights of use) fall an average 53 per cent a year between 1997 and

2001, according to analysts Jardine Fleming. An IRU is an industry unit that

measures the proportions of a cable's total capacity owned by any buyer.

Over the short term, overcapacity may

actually work to the advantage of operators like C2C. Mr Matsudaira says that

carriers are cautious about buying IRUs outright and prefer to rent them instead

as a leased line service which enjoys better margins.

C2C has laid a 17,000 km cable that links

Singapore with Japan, South Korea, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

C2C is owned 59.5 per cent by SingTel, and a consortium of partners, including

US-owned Tycom Asia Networks (15 per cent), Hong Kong- based New Century Globe

Telecom (6.37 per cent), Hong Kong based- iAdvantage, Japan-based KDDI and the

Philippines-based Globe Telecom (4.125 per cent each).

For its fiscal Q1 ended June 2002, SingTel

grossed $307 million in data-related revenues. These formed about 26 per cent of

SingTel's overall operating revenue (net of Optus), and was the largest

contributor to SingTel's revenues. However, data revenues showed significant

price erosion - they grew only 2 per cent in its Q1 year-on-year. But data

volumes shot up 72 per cent during this period.

- Singapore Business Times

23 Sept 2002

Asians

likely to overtake Americans on the Web

Almost half of the world's

population of Internet users will come from Asia by 2003, with China leading the

surge

MELBOURNE -

The number of

Asians connected to the Internet, particularly in China, is poised to surge past

the US in the next few years, executives told the World Economic Forum's

Asia-Pacific summit.

Asia will make up almost half

the world's population connected to the Internet by 2003 as the region's

countries build new telecommunications networks to handle more users, said Mr

Masayoshi Son, president of Softbank, Japan's biggest Internet-related investor.

He said the number of people

using the Internet worldwide will probably rise to one billion in three years

from 300 million users currently, with most new users coming from Asia.

That presents an opportunity

for companies in Asia developing new technologies that support the Internet,

including electronic business-to-business trading, he said.

Others agree Asia will

dominate world growth in Internet usage, with television and other wireless

applications expected to be a major source of Internet delivery.

""The current

growth rates indicate that Asia is actually growing faster, in both the number

of Internet service providers and the number of people getting

inter-connected,'' said Mr Eric Schmidt, chief executive at Novell, a US maker

of computer-network management software.

""Current growth

rates of the Internet outside the US in general are faster than they are in the

US, which I think is a good thing,'' he told the forum.

""I think the

message is very good for Asia.''

Earlier, Telstra chief

executive Ziggy Switkowski said that the adoption of technology to social and

commercial applications is well advanced in parts of Asia.

Melbourne-based Telstra is

Australia's No 1 Internet company.

""We shouldn't make

the assumption that Asia is at a very early stage of development, because in a

number of countries and a large number of applications, the progress that is

evident is quite formidable,'' he said.

It is estimated Japan has 27

million Internet users, ahead of China with 16.9 million users and South Korea

with 15.3 million. Australia has 7.3 million.

Accounting firm Deloitte

Touche Tohmatsu released a survey, saying Asian Internet users are growing at a

compound rate of about 45 per cent.

It said that China is

expected to double its number of users every six months, a rate of growth that

could lead China to boast the world's biggest online population within 10 years.

""The potential for

Asia, and in particular China, to overtake the west in terms of e-commerce

uptake is not a matter of if, but when,'' said Mr Peter Williams, an e-business

practice partner at Deloitte. --Bloomberg

News 2002

U.S. Web Giants Target

China

As China's internet market sizzles -- 94 million

Chinese now go online, second only to the U.S. -- many of its Web companies have

rocketed from startup obscurity to stock-market fame. Shanghai gaming innovator

Shanda Interactive Entertainment Ltdl ast year raised $100 million in an initial

public offering and now stands 249% above its launch price. Ctrip.com which

provides online travel reservations, raised $40 million in an initial public

offering in December, 2003, and its shares have since more than doubled. Tencent,

which operates China's top instant-messaging service, pulled in $200 million in

its Hong Kong IPO last June and has seen its shares rise by 30%.

Now, Net giants from the U.S. want a piece of that

China magic. On May 11, Microsoft Corp.said its MSN portal had formed a joint

venture with a Shanghai company to operate a Chinese-language version of MSN.

Later in the month, Google Inc.opened a small office in Shanghai, following a

February deal with Tencent to provide search services for the Chinese company.

And Yahoo! Amazon.com , eBay , and Expedia have been on the

prowl in China, too. "The sense of urgency among big players has

accelerated," says Safa Rashtchy, an analyst with Piper Jaffray & Co.

in Menlo Park, Calif. "If you don't have a major stake in China, you could

be left out."

It helps that U.S. Net outfits have an easier time getting into China these

days. In the past, foreign companies that wanted to invest in Chinese dot-coms

had to grapple with restrictions limiting their access to the market. Typically,

the Americans would invest in an offshore company that had a contract to provide

content to the Chinese company but had no stake in China itself. In late 2003,

Beijing eased those restrictions as part of commitments it made in joining the

World Trade Organization. Foreigners can now directly own 50% of Chinese Net

companies, though getting approvals can still be slow.

The first to take advantage of the more liberal climate is MSN. Its partner is

Shanghai Alliance Investment Ltd., which is run by Jiang Mianheng, a son of

former President Jiang Zemin. The venture will offer Chinese-language content

from government-backed outlets such as the Beijing Youth Daily and the

Shanghai Media Group. One target audience is China's 340 million-plus cellular

subscribers, who often use their handsets to go online. "Because of the

mobile population, there are opportunities for new services," says Bruce

Jaffe, MSN's chief financial officer. One such service, for instance, might

allow Chinese bloggers to post their thoughts while on the go.

Other U.S. companies have already jumped in, restrictions or no. Yahoo! Inc.

last year paid $120 million for a Hong Kong company that gives it control of

Chinese search engine 3721. A key attraction of 3721 was the relationships its

sales staff had built up with advertisers, says John E. Marcom Jr., senior

vice-president of international operations at Yahoo. "3721 has a thriving,

on-the-ground sales model," says Marcom. In addition, 3721 understands the

local market and has helped Yahoo spruce up its site design and product

positioning, he says.

Yahoo's salespeople will have to work hard to stay ahead of Google. The search

giant sold about $24 million in ads in China last year and had about a quarter

of the search market, according to researchers BDA China Ltd. While other search

engines typically charge 3.6 cents a click for ads pegged to keywords, Google in

recent months has cut the price to just 2.4 cents. While that could well get

more companies interested in buying keyword ads, it is also likely to put

pressure on China's leading search company, Baidu, in which Google holds a small

stake.

Big e-commerce players are moving into China, too. eBay Inc. paid $180 million

for EachNet Inc., a Delaware company that gives it control of Chinese Net

auctioneer EachNet, and says it will spend at least $100 million in China this

year. China is a "defining measure of business success on the Net,"

Chief Executive Margaret C. "Meg" Whitman told analysts in February.

EachNet's gross sales grew 70% year-on-year in the first quarter, to $100

million. And last August, Amazon.com Inc. bought a British Virgin Islands

company that gives it control of Joyo.com, China's leading online bookseller,

for $75 million. While Amazon CEO Jeffrey P. Bezos cautioned shareholders at the

company's May 17 annual meeting that the venture "will take many years to

succeed," he said "it's an investment worth making in a country that's

growing so rapidly."

Some Chinese are welcoming the American invasion. Pony Ma is the 34-year-old

founder and CEO of Tencent, the Shenzhen company that operates QQ, an

instant-messaging service with 77% of the Chinese IM market. Although Ma first

turned to Baidu for a search function on the QQ portal, in February he switched

to Google. Ma thought Google's search engine was more efficient, and decided it

was less risky to work with the Americans. "Baidu could be a

competitor," Ma explains. Given what he sees as the more limited goals of

the newcomers, he says, "it's safer to work with foreign companies."

Foreigners, though, face plenty of dangers in China. For starters, the market is

immature. Paid search, for instance, is just a $150 million market, compared

with $3.9 billion in the U.S. In addition, companies that don't have a local

operation can find themselves at a big disadvantage. For instance, Google

doesn't have any local servers; as a result, few university students can see it,

because school networks don't easily connect to sites outside China. And keeping

the country's censors satisfied that the Net isn't fostering subversion requires

companies to do lots of monitoring of content on their sites.

At MSN, Jaffe says the company is doing its best to make sure that the censors

have no reason to move. "We keep a keen eye on being locally

sensitive" wherever MSN operates, he says. "This will be no

different." That will mean restrictions on what Chinese Net surfers can see

and say on MSN's site, of course. But it's a price Microsoft and much of the

rest of the U.S. Internet community appear willing to pay. -

By Bruce Einhorn in Shenzhen, with Ben Elgin and Robert D. Hof in San Mateo,

Calif. and Timothy J. Mullaney in New York BUSINESS

WEEK 13 June 2005

The net imperative

The net imperative

In five years’ time, says Andy Grove, the chairman

of Intel, all companies will be Internet companies, or they won’t be companies

at all. Just another example of the arrogance and exaggeration the

information-technology industry is notorious for? Yes, in the sense that Mr

Grove is as keen as the next chip maker to scare customers into buying his

products. No, in the sense that, allowing for a little artistic licence, he is

probably right.

The Internet is said to be both over-hyped and

undervalued. Ask any signed-up member of the “digirati”, and you will be

told that the Internet is the most transforming invention in human history. It

has the capacity to change everything—the way we work, the way we learn and

play, even, maybe, the way we sleep or have sex. What is more, it is doing so at

far greater speed than the other great disruptive technologies of the 20th

century, such as electricity, the telephone and the car.

Yet, nearly five years since the Internet developed

mass-market potential with the invention of a simple-to-use browser for surfing

the World Wide Web, it is easy to overstate its effect on the daily lives of

ordinary people. Even in the United States, the most wired country in the world,

most people still lack, or choose not to have, Internet access. And even for

most of those who have access both at home and in the office, the Internet has

proved more of an addition to their lives—sometimes useful, sometimes

entertaining, often frustrating—than a genuine transformation.

Everybody loves e-mail; if you are a teenage girl,

chat is cool; and the ability to retrieve information about so many things is

truly miraculous, even if search engines are a bit clunky. Despite early

misgivings about credit-card security, buying certain kinds of things on the

web—for example, books, CDs and personal computers—is

convenient and economical, and has become popular. All these things are

certainly nice to have, but they could hardly be called revolutionary.

But while the media have concentrated on just a few

aspects of the web—the glamorous consumer side of content and shopping on the

one hand, and the seamy end of pornography and extremist rantings on the

other—something much more important is happening behind the scenes:

e-business. The Internet is turning business upside down and inside out. It is

fundamentally changing the way companies operate, whether in high-tech or

metal-bashing. This goes far beyond buying and selling over the Internet, or

e-commerce, and deep into the processes and culture of an enterprise.

From e-commerce to e-business

Some companies are using the Internet to make

direct connections with their customers for the first time. Others are using

secure Internet connections to intensify relations with some of their trading

partners, and using the Internet’s reach and ubiquity to request quotes or

sell off perishable stocks of goods or services by auction. Entirely new

companies and business models are emerging in industries ranging from chemicals

to road haulage to bring together buyers and sellers in super-efficient new

electronic marketplaces.

The Internet is helping companies to lower

costs dramatically across their supply and demand chains, take their customer

service into a different league, enter new markets, create additional revenue

streams and redefine their business relationships. What Mr Grove was really

saying was that if in five years’ time a company is not using the Internet to

do some or all of these things, it will be destroyed by competitors who are

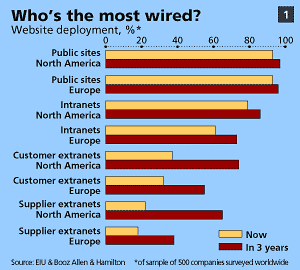

Most senior managers no longer need convincing. A

recent worldwide survey of 500 large companies carried out jointly by the

Economist Intelligence Unit (a sister company of The Economist) and Booz

Allen and Hamilton, a consultancy, found that more than 90% of top managers

believe the Internet will transform or have a big impact on the global

marketplace by 2001.

That message is endorsed by Forrester Research, a

fashionable high-tech consultancy. It argues that e-business in America is about

to reach a threshold from which it will accelerate into “hyper-growth”.

Inter-company trade of goods over the Internet, it forecasts, will double every

year over the next five years, surging from $43 billion last year to $1.3

trillion in 2003. If the value of services exchanged or booked online were

included as well, the figures would be more staggering still.

That makes Forrester’s forecasts of

business-to-consumer e-commerce over the same period—a rise from $8 billion to

$108 billion—look positively modest. There are two explanations:

business-to-business spending in the economy is far larger than consumer

spending, and businesses are more willing and able than individuals to use the

Internet.

Forrester expects Britain and Germany to go into the

same hyper-growth stage of e-business about two years after America, with Japan,

France and Italy a further two years behind. And just as countries will move

into e-business hyper-growth at different times, so too will whole industries.

For example, computing and electronics embraced the Internet early and will

therefore reach critical mass earlier than the rest. Aerospace, telecoms and

cars are not far behind. Other conditions for early take-off include the ready

availability of the right kind of software, computing platforms and

systems-integration expertise.

Just as crucial is the impact of so-called “network

effects” as online business moves from a handful of evangelising companies

with strong market clout, such as Cisco Systems, General Electric, Dell, Ford

and Visa, to myriad suppliers and customers. As both buyers and sellers reduce

their costs and increase their efficiency by investing in the capacity to do

business on the Internet, it is in their interest to persuade more and more of

their business partners to do the same, thus creating a self-reinforcing circle.

However, even within particular industries companies

are moving at different speeds. Much depends on the competition they are exposed

to, both from fast-moving traditional rivals and from Internet-based newcomers.

But nobody can afford to be complacent. Successful new e-businesses can emerge

from nowhere. Recent experience suggests it takes little more than two years for

such a start-up to formulate an innovative business idea, establish a web

presence and begin to dominate its chosen sector. By then it may be too late for

slow-moving traditional businesses to respond.

For evidence of how far most companies still have to

go in developing their Internet strategies, look no further than their corporate

websites. A few pioneers—such as Charles Schwab in stockbroking and Dell in

the PC business—have successfully transferred many of

their core activities to the web, and some others may be trying their hand at a

few web transactions, with an eye on developing their site as an extra

distribution channel later. But more often than not, those websites are stodgily

designed billboards, known in the business as “brochureware”, which do

little more than provide customers and suppliers with some fairly basic

information about the company and its products.

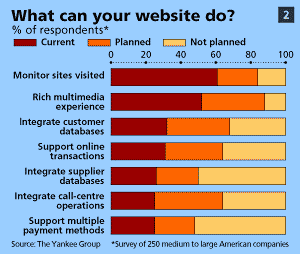

Most managers know perfectly well that they have to do

better. The Yankee Group, another technology consultancy, earlier this year

questioned 250 large and medium-sized American companies across a broad range of

industries about their views on e-business, and found that 58% of corporate

decision makers considered the web to be important or very important to their

business strategy. Only 13% thought it not important at all. A large majority

(83%) named “building brand awareness” and “providing marketing

information” as key tasks for their websites, and almost as many (77%) thought

the web was important for generating revenue. A smaller majority (57%) also saw

its potential for cutting costs in sales and customer support. Yet despite all

this positive talk, three-quarters did not yet have websites that would support

online transactions or tie in with their customer databases and those of their

suppliers, although many were working on it.

In other words, most bosses know what they should be

doing, but have not yet got around to it. It is easy to understand why. Knowing

that you need a coherent e-business strategy is one thing, getting one is

altogether more difficult. And until you decide precisely what your strategy

should be, it will not be clear what kind of IT

infrastructure investments you will need to make.

Here we go again

All this gives many managers a terrible sense of

déjà vu. They have been through outsourcing, downsizing and

re-engineering. They may well have undergone the frequently nightmarish

experience of putting in the packaged information-technology (IT)

applications that automate internal processes and manage supply chains,

known collectively as “enterprise resource planning” (ERP),

and are still wondering whether it was worth spending all those millions of

dollars. Nearly all of them embraced the low cost and flexibility of PC-based

so-called client/server computing at the start of the 1990s, only to discover

the perils of decentralising data and distributing complexity. And over the past

couple of years, they have invested lots of time and money into nothing more

exciting than the hope of avoiding a systems meltdown on the first day of the

new millennium.

So they have reason to be wary of consultants

and visionaries who promise new paradigms and tidal-wave technology. A recent

survey of chief executives’ attitudes to IT conducted

by the London School of Economics for Compass America found that only 25%

believed that it had made a significant contribution to the bottom line, and

more than 80% had been disappointed by its contribution to their company’s

competitiveness.

No wonder many of them are asking themselves

whether e-business is the most exciting opportunity or the most terrifying

challenge they have ever faced. Yet most of them know that the Internet is in an

entirely different category from the technology-driven changes they have either

embraced or had thrust on them in the past. The same survey suggested that the

Internet has significantly changed expectations about what IT

could deliver, with more than half of the top managers saying they had high

expectations for the future.

Part of the explanation is that IT

investments, particularly ERP, have been inward-looking,

concentrating on making each enterprise more efficient in isolation. By

contrast, the Internet is all about communicating, connecting and transacting

with the outside world. With e-business, the benefits come not just from

speeding up and automating a company’s own internal processes but from its

ability to spread the efficiency gains to the business systems of its suppliers

and customers. The ability to collaborate with others may be just as much of a

competitive advantage as the ability to deploy the technology. Certainly the

technology matters, but getting the business strategy right matters even more.

And that may mean not just re-engineering your company, but reinventing it.

- ECONOMIST

1999

Dotcom Mania

Time Magazine Asia Cover Story

7 Feb 2000

As Asia's Internet start-ups race toward lucrative

listings, investors have dollar signs in their eyes

And now it's Asia's turn. The

continent of economic miracles has watched, stunned from a distance, as the

Internet-driven New Economy mushroomed in the West. Silicon Valley whipped up

America's emerging market within: a roaring, just-wing-it, bandwagon-cum-bubble

business culture that has looked a lot like, well, the freewheeling Asia of the

past. For a while, it seemed as if the long-predicted Pacific Century might be

stillborn--or stolen altogether.

No longer, and Silicon Valley beware.

Asia is producing its own Net nerds bringing new businesses and technologies to

the region and, along the way, getting rich beyond their wildest dreams. If all

works out, young geeky pioneers in Japan, China, Korea, India, Singapore and

Taiwan may re-invent Asia's future--just in time. "It's remarkable,"

says Sandra Morris, director of chip giant Intel's e-commerce unit. "The

development line in Asia almost identically follows that of the U.S., only it's

2-3 years behind." And catching up with lightning speed. Internet analyst

Greg Tarr in Singapore estimates that there will be 200 Net-related IPOs in Asia

this year, half of them in Japan.

It's no surprise Asia is

embracing the New Economy model. Just check out what's been going on across the

Pacific. New York's NASDAQ index, loaded with technology and Internet stocks,

soared 85% in 1999, fueled by $70 billion in new floats--a figure equal to

Malaysia's GDP. If the share price of Yahoo!, the Net search-engine company now

valued at $82 billion, climbs this year as it did last, the company will be as

big as the Australian economy. That's how the New Economy compares with the old,

and until recently, Asia was about as racy as a 2.4K modem.

Though it may now seem that everyone is making huge piles of money, the big

returns aren't automatic. For every Internet success story, there are countless

failures. To succeed, a venture has to be conceptually brilliant, quick off the

mark and able to woo investors. In the following pages, we'll take you through

the various stages of a successful Internet play, from being a promising

start-up; to winning financial backing from an "angel" investor and,

subsequently, a venture capitalist; to maturing under the guidance of an

"incubator"; and finally becoming ready for the big payout: either a

stock market listing or simply selling the company.

Fortunes will be made. Richard Li's Pacific Century CyberWorks group, a kind of

Asian Internet mutual fund, last week announced yet another deal: a joint

venture with CMGI to develop Asian versions of the American company's Internet

brands, like Lycos, AltaVista and AdForce. PCCW is now priced as one of Hong

Kong's biggest companies; a year ago it didn't exist. Its profits so far: zip.

In Singapore, Chua Kee Lock had a net worth last year of $250,000, if you

counted his car and pension fund. Today, he's CEO of a (profitless) Internet

telephony company and has a personal net worth of $6 million. To prepare for the

high rolling that's to come, NASDAQ-style exchanges are appearing in Hong Kong,

Shanghai and Tokyo.

Fortunes will be lost as well in the market gyrations that are already wracking

the region. But risk is what Asia has always excelled in. "The Pacific

Century has not been lost," says Singaporean Netrepreneur Wong Toon King,

"only delayed a bit." A brand new future? A bubble beyond anything

we've seen in the past? A bit of both? Brace yourself: by any standard, Asia's

New Economy is going to provide a wild and thrilling ride.

- Time

Asia

Portal

start-ups race to beat rules

Internet

companies are racing to beat expected new rules that will regulate foreign

investment in the mainland sector

Two

new portals announced sites yesterday.

ChinaRen.com

and eLong.com, both based in the United States and financed by American

investors, are defying the present hazy rule forbidding foreign investment in

the lucrative sector.

As

no one can say what the new rules being drafted will be like, the companies are

launching their services with breakneck speed.

"This

is the time to get into China . . . For late starters, it might be difficult to

find investors, because the rules . . . might change," Joseph Chen,

chairman and chief executive of ChinaRen.com said.

He

and two classmates from Stanford University generated the idea in January,

raised US$3 million in a two to three-month period and launched the site in

August.

The

company's Beijing offices still have not been furnished.

The

mainland recently reaffirmed a ban on foreign investment on the Internet sector

but has not taken any action against foreign-funded companies already doing

business in there.

Reports

say new rules are being drafted that will clarify whether foreign investors can

invest in the market.

Speculation

is rife, with some predicting that Beijing will require Web sites to be licensed

and the licences to be renewed.

Others

believe the government will not issue licences to sites that offer foreign news.

The

murky nature of the Internet sector in the mainland was making companies and

investors nervous, Mr Chen said.

But

he was optimistic the government would not cut out foreign investment.

"Capital

plays a very important role in China. China needs a lot of capital. For any

industry, foreign sources of capital would bring talent from the originating

company, including technology, experience and management methods," Mr Chen

said.

ChinaRen.com

and eLong.com both play up the fact that the companies' founders are returning

Chinese - AGENCE

FRANCE-PRESSE in Beijing November 10, 1999

Cyber-squatters cash in on leading trademarks

They are called "cybersquatters" - people who

register Web addresses resembling well-known trademarks hoping to sell them

later at a premium.

They find work more difficult in Hong Kong because the

Chinese University, which registers domain names within the SAR, requires proof

of legitimate company connections.

However, people can get around that by registering

overseas.

"There is really very little companies can do to

protect themselves in terms of domain names," said Productivity Council

principal information technology consultant Roy Ko Wai-tak.

But he said he had not heard of a case where someone

paid for a domain name so he could file a public complaint against a company on

the Web site.

He was speaking after Internet business consultant

Julius Moltgen - who claimed guests at his hotel wedding banquet suffered food

poisoning - took revenge on hotel owners Sun Hung Kai Properties by buying the

Web site www.sunhungkai.com and using it to air his complaints.

Mr Ko said there was no law to stop Mr Moltgen.

"The contents are subject only to the usual laws

on libel. There is a very weak legal basis to argue such cases as trademark

infringement. Domain name registration works on a first-come, first-serve

basis."

Mr Ko said cases were usually settled out of court.

One way to protect yourself is to follow the example

of Pacific Century CyberWorks, which has registered a long list of variations on

its name.

Another is to pay a lot of money to buy back your

Internet names.

Last year US securities firm Morgan Stanley Dean

Witter offered US$10,000 (HK$78,000) to a teenager for msdwonline.com.

In November a Briton registered the domain names of

six Asian countries, including Governmentofsingapore.com and offered to sell

them for US$10,000.

IKEA is suing mainland company Beijing Guowang

Information in a mainland court because the latter has registered http://www.ikea.com.cn/.

- by Alex Lo South

China Morning Post 15 Feb 2000

Size

Does Matter in Asia's Cyber Race

From Singapore to Taipei, old-line conglomerates

are crowding out the nimble newcomers

Can't get enough of U.S. Internet stocks--the ones

with weak profits and outrageous prices? There's always Wharf Holdings Ltd. in

Hong Kong. The $1.3 billion conglomerate has seen property prices plunge and

business shrink at its hotels and stores. It's also taking big losses on its

push into phone service and cable TV. Yet Wharf's stock price has nearly doubled

since Apr. 1, to $2.68 on May 5. The reason: Wharf has recast itself as an

Internet play. ''The Internet market will continue to grow,'' explains Daniel

Ng, director of Wharf's Internet division. ''With our strength, we should be

able to find our position in it.''

The Internet craze is sweeping across the Pacific. From Singapore to South

Korea, shares with even vague links to cyberspace are torrid these days and

adding to the euphoria in Asia's bourses. But the fever is proving a decidedly

local strain. Unlike the U.S. scene, dominated by small, zippy startups, Asia's

Net boom is tilted toward old-line conglomerates with established reach. Some

venturesome high-tech companies plan to issue stock. But for now, the market is

rewarding size more than agility. ''In the U.S. Internet boom, everyone can

catch the wave,'' says Antonio Tambunan, who manages the Internet advisory group

for Deloitte & Touche Corporate Finance in Hong Kong. ''In Asia, that wave's

reserved for the big boys.''

That's because Asia has almost no pure Net plays. Like Wharf, just about every

Net stock in the region bears heavy non-Net baggage. Asia has no NASDAQs,

either. Most Asian markets are just setting up second boards--which makes it

tough for startups to find capital. In effect, East Asia is passing through a

phase the U.S. left a few years ago. Back then, Internet service providers

(ISPs) such as Netcom were all the rage in the U.S. market. Today, while there

are Asian versions of portals such as Yahoo! Inc. and E-commerce companies

such as Amazon.com Inc. none is publicly traded yet.

Wharf is typical of the alternatives open to investors. Its monopoly cable-TV

network reaches 700,000 homes. In March, Wharf said that it will use the

network to provide high-speed Internet access by yearend. Although the Internet

is likely to remain a small part of Wharf's revenues, that was enough to send

the stock soaring. Other Asian conglomerates are placing similar bets. In April,

Sumitomo Corp. announced a joint venture with AtHome to offer cable-modem access

in Japan.

Even the few Asian startups that have gone public are exceptions that prove the

rule. Singapore's Pacific Internet, a regional ISP, had an initial public

offering on the NASDAQ in February. Its stock has since risen 30%, to 62 on May

5. But Pacific Internet is a unit of Sembcorp Industries, a state-owned

conglomerate with enough muscle to support a newcomer through its infancy.

Another beneficiary of deep-pocketed parents is Yahoo Japan, backed by Yahoo!

and Japanese IT giant Softbank Corp. Shares in Hong Kong's Tricom Holdings, a

telecom services provider, soared 1,246% on May 4 after it was taken over by

Pacific Century, controlled by Richard Li, son of billionaire Li Ka-shing. The

young Li plans to use Tricom to develop IT businesses.

ISP BAN. Without such backing, most startups are finding Internet fever

has come too soon for them to take advantage of it. And raising equity capital

is only one problem for aspiring Net players. Protected markets are another.

Singapore's Pacific Internet has a quasi-monopoly with two other state-backed

ISPs, Singnet and Cyberway. Last year, the Singapore government let

new players into the market, but it still bans foreigners from controlling a

local ISP.

In Hong Kong, Kevin Randolph knows what it's like to go up against entrenched

market leaders. As president and CEO of Asia Online, an unlisted ISP with

operations in Hong Kong and the Philippines, Randolph is challenging Hong Kong

Telecom, which counts more than half the territory's 600,000 Internet

subscribers as customers. Asia Online wants to offer high-speed access over

phone lines. Since Softbank acquired his firm in February, Randolph has the

backing he needs. But the government won't license him to sell high-speed access

over existing phone wires--so he can't compete with Hong Kong Telecom, Wharf,

and the two other fixed-line operators. On May 5, Hong Kong announced it would

not allow newcomers to own local networks before 2002.

That leaves Randolph with little choice but to lease wires from Hong Kong

Telecom, which has the only broadband service in town and charges rivals $70 a

month per customer for access--more than twice what it charges its own

subscribers. ''The incumbent out here has an extraordinary lock on the market,''

Randolph says. That seems just as true in South Korea. Korea Telecom is spending

$300 million to provide the country's fastest Net access.

It might not be much easier when the battle shifts from infrastructure to

content. In the U.S., most ISPs never tried to become content providers. That

left an opening for companies such as Yahoo! But the big Asian ISPs want to echo

the success of Yahoo! and America Online Inc.--and freeze out any portal

startups. In April, Hong Kong Telecom opened a Chinese-language portal intended

to keep subscribers from venturing to sites such as Hongkong.com, backed by the

Xinhua news agency. It opened an English site on May 3.

BIG BACKERS. Despite the obstacles, new portals are still trying to make

their mark in Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan. Some have attracted venture capital.

Sina, with offices in Taipei, Beijing, and Silicon Valley, claims a daily

average of 4.6 million page views on its sites. It just won backing from Goldman

Sachs and Softbank. Sohu, a Sina rival in Beijing, is supported by such

investors as Intel and International Data Corp.

Zhaodaola Internet (Beijing) Ltd. has some novel backers: Its controlling

partners include U.S. televangelist Pat Robertson. Its site, Zhaodaola!

(Mandarin for ''I've found it!'') offers a cybermenu with a men's fashion,

sports, and health section called ''Macho Man.'' All the portals ''are in a race

to [make an] IPO first,'' says Ted Dean, a consultant for BDA China, an Internet

consultancy in Beijing. Also among the aspirants is Yahoo Korea. Says Yook J.

Dong, an analyst at CSFB in Seoul: ''Everyone is thinking about listing now.''

Few startups will issue stock before midyear. Even then, they may be

overshadowed. Industry sources say that Hong Kong Telecom is mulling a NASDAQ

listing for its Internet subsidiary. So is Korean market leader Dacom. Asia's

Internet race has barely begun. For now, most investors with a craving for the

Asian Internet will head toward companies with established connections. -

By Bruce Einhorn in Hong Kong, with Michael Shari in Singapore and Jennifer

Veale in Seoul Business

Week 17 May 1999

Wide Swath of China Is Surfing the

Internet

Internet use is spreading farther than

expected in China, reaching smaller, less-developed cities, and would likely be

even more popular if not for government controls, according to two surveys.

The surveys, conducted by the

government-backed Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, are the most extensive on

Internet usage in China to date. Researchers interviewed 4,100 people in 12

cities, from the major urban centers on the prosperous coast to interior towns

where economic growth has lagged. The surveys show that Internet penetration is

on average highest in the metropolises of Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou --

where one-third of all residents use the Internet -- but small cities of around

100,000 in population ranked a surprising second, with 27% of residents going

online. That percentage surpasses the 24% rate in four leading industrial

provincial capitals, according to the surveys.

Underpinning the growth in small cities

is an array of factors, including government policies and free-market

competition to provide Internet services, says one of the surveys, on small

cities. In Yima, a city in hilly, rural Henan province, for example, a mining

company vied with the local subsidiary of China's telecom authority to offer

Internet services starting in the late 1990s. The result was low-cost Internet

connections and a surge in Internet cafes -- 60 of them by early 2002 -- for a

city of 120,000 where incomes average $500 a year and many residents can't

afford a home computer

The findings, say the researchers who

conducted the study, suggest that the Internet's impact is greater than

previously thought, with implications for the future of the economy and the

communist government. Far from being a tool of the educated and well-off in big

cities, the Internet is cutting across income and geographical lines in China,

creating a populace that is better informed and more demanding of the

government, the researchers say. "The Internet's emergence has filled a

void," Hu Xianhong of Peking University wrote in the survey on small

cities.

Overall, the surveys found that 56% of

the 68 million Internet users in China are male, and 58.2% are between the ages

of 17 and 24. Nearly 40%, who are either students or unemployed, have no monthly

income, which has a damping effect on electronic commerce. Only one in five

Internet users has made a purchase online, and most are for small items such as

books or movie tickets. However, nearly 12% of online orders were for the

purchase of computers.

The surveys also include good news for

China's three Nasdaq-listed portals -- Netease.com

Inc., Sina

Corp. and Sohu.com

Inc. -- which are the most frequently used services for accessing Web sites. And

Chinese users spend most of their Internet time browsing Web pages and reading

news.

This emerging online community,

according to the surveys, shares ideas that could pose a challenge to a

government often bent on control. More than 85% recognize a role for the

government in managing and controlling the Internet, and most are concerned

about pornographic and violent content. But fewer than 13%, the survey says,

believe that the government should police political content, and overwhelmingly

people see the Internet as a medium allowing greater freedom of speech and

criticism of government policies.

"Most people strongly believe that

the Internet will affect Chinese politics," says the study on Internet

usage, authored by Guo Liang, considered a leading authority on the Internet's

social impact in China.

Authorities, however, have sought to

rein in this impulse, targeting for arrest those who disseminate dissenting

opinions online. Last week, a civil servant in Hubei province, Du Daobin, was

formally arrested on subversion charges for posting essays critical of the

government and for organizing a petition protesting the detention of another

Internet activist.

The surveys suggest that Internet usage

would likely be even more widespread without government controls. In the small

cities and provincial capitals, less-affluent populations rely on Internet

cafes, the surveys say, and a crackdown last year has led to closings, reducing

the number of outlets. In Yima city, the government canceled all licenses and

limited the number of new ones it issued to 38 establishments, though some

outlets operate illegally. The government, the survey says, has decided that

Internet cafes should be limited to one for every 10,000 residents.

- By Charles Hutzler Staff RReporter at Asian

Wall Street Journal

18 Nov 2003

Hong Kong high users of Net

Hong Kong Kong

people are among the highest users of Internet radio and audio-visual content,

thanks to a high penetration of broadband access.

In the latest ratings by ACNielsen and

NetRatings, the SAR was second only to Brazil in Internet radio usage of 12

countries studied, and fourth highest in viewing audio-visual content.

``In most countries in this report, a 56K

modem is the most popular tool to access the Internet. However, in Hong Kong, an

astonishing 58 per cent of those who responded and have Internet access use

either a cable modem or high-speed telephone connection,'' ACNielsen eRatings

director Peter Steyn said.

``You have a better Internet experience with

broadband, so there's higher usage for things like Internet radio and visual

content.''

The survey, of 1,500 Internet users in each

country, found email to be the dominant online activity, with an average of 85

per cent of those surveyed having used it.

The survey said email's popularity was

because it was a cost-effective way to communicate across long distances and did

not require high-speed connections.

The use of instant messaging, such as ICQ,

was relatively low in Hong Kong, which was seventh on the list with 26 per cent

of people having used the application in the past six months.

``Instant messaging is a great way to

communicate person-to-person. It's especially popular in large countries where

long distance rates are high. Perhaps that's why it isn't widely used in Hong

Kong. Usually it's just easier to pick up the phone to call someone,'' Steyn

said.

The report studied people aged 16 or

older who had used the Internet in the past six months. Hong Kong was the only

Asian territory in the survey. -

HK STANDARD 11 May 2002

China's

Technology

SemiAnnual Survey Report On Internet

Development In China (2000.1)

Statistics on Internet development in China, including

the total number of hosts and users, user geographic distribution, traffic

pattern, and domain name registration etc, are very significant and valuable in

helping government agencies and commercial enterprises in making their policy

and business decisions. In 1997, the State Council's Informatization Office and

the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) Working Committee

determined that the CNNIC, in cooperation with the four major networks units in

China, would carry out surveys on Internet development in China.

CNNIC published its four previous reports

("Survey Report on Internet Development In China") in November 1997,

July 1998, January 1999 and July 1999. These survey reports were well accepted

by the general public both in China and in other countries. They were widely

cited as the leading authority on China's Internet statistics. Users, government

organizations, enterprises and news media request the CNNIC to regularly do it

and publish the results. To satisfy the needs of the public, CNNIC decides to do

the survey as a semiannual activity. The surveys will be conducted and published

in January and July of each year.

The current survey covered many aspects of China's

Internet, including total user number, total host number, number and

distribution of domain names, international bandwidth for each of the

networks, and total number of WWW sites. The user information are statistically

derived from the data collected through online survey. Internet and Web usage

statistics, as well as users' opinions on current hot issues, have also been

obtained through the online.

Like the previous reports from the CNNIC, the survey

has closely followed the methodologies adopted in other countries. Data is

collected through submitting online questionnaires on popular Web sites and

conducting software-driven online seeking. CNNIC conducted its online survey in

December 15-31, 1999. Survey questionnaires were placed on the home pages of

famous Web sites in China. The survey is strongly supported by almost all the

well-known Chinese ISPs and ICPs. The online survey received 363,538 responses.

Among these responses, 202,432 were valid and used to calculate the final

results. The number of valid respondents has increased tremendously, compared to

the previous four surveys. The increase has greatly enhanced the accuracy of

survey results.

1.Computer Hosts in China: 3,500,000. Among them,

410,000 are connected through leased lines and 3,090,000 are through dial-up

connections.

2.Internet Users in China: 8,900,000. Among them,

1,090,000 are through leased line connections, 6,660,000 are dial-up users and

1,150,000 use both. Besides the computer, users that use other equipment (for

example mobile telephone, PDA and top-set) are 200,000.

3.Domain Names Registered In The Top-Level Domain

"CN":

|

|

AC

|

COM

|

EDU

|

GOV

|

NET

|

ORG

|

AADN

|

Total

|

|

Number

|

500

|

38776

|

731

|

2479

|

3753

|

940

|

1516

|

48695

|

*AADN = Administration Area Domain Name

The distribution of domain names by second-level of

domain names£º

The distribution of domain names by geographic

locations (provinces)

|

|

Beijing

|

Shanghai

|

Tianjin

|

Chongqing

|

Hebei

|

Shanxi

|

Neimenggu

|

|

Domain Names

|

17871

|

4284

|

855

|

347

|

821

|

298

|

221

|

|

Percentage

|

36.7%

|

8.9%

|

1.76%

|

0.81%

|

1.79%

|

0.61%

|

0.45%

|

|

|

Liaoning

|

Jilin

|

Heilongjiang

|

Jiangsu

|

Zhejiang

|

Anhui

|

Fujian

|

|

Domain Names

|

1223

|

273

|

417

|

2362

|

2094

|

347

|

1167

|

|

Percentage

|

2.6%

|

0.56%

|

0.86%

|

4.85%

|

4.4%

|

0.71%

|

2.5%

|

|

|

Jiangxi

|

Shangdong

|

Henan

|

Hubei

|

Hunan

|

Guangdong

|

Guangxi

|

|

Domain Names

|

205

|

2353

|

1130

|

891

|

407

|

7043

|

464

|

|

Percentage

|

0.42%

|

4.83%

|

2.32%

|

1.83%

|

0.94%

|

14.46%

|

0.95%

|

|

|

Hainan

|

Sichuan

|

Guizhou

|

Yunnan

|

Tibet

|

Shanxi

|

Gansu

|

|

Domain Names

|

359

|

751

|

120

|

756

|

15

|

680

|

185

|

|

Percentage

|

0.74%

|

1.54%

|

0.25%

|

1.55%

|

0.03%

|

1.5%

|

0.38%

|

|

|

Qinghai

|

Ningxia

|

Xinjiang

|

HongKong

|

Macou

|

Taiwan

|

|

Domain Names

|

21

|

44

|

212

|

87

|

0

|

3

|

|

Percentage

|

0.04%

|

0.09%

|

0.44%

|

0.18%

|

0

|

0.01%

|

4. Number of Websites in China: 15153

(approximate)

5. Total Bandwidth of Leased International

Connections: 351M. Countries directly interconnected to China's Internet

include the United States, Canada, Australia, Britain, Germany, France, Japan,

South Korea, etc. The detailed distribution among Interconnecting Networks is as

follows.

|

|

CSTNET

|

CERNET

|

CHINANET

|

CHINAGBN

|

UNINET

|

Total

|

|

Bandwidth

|

10M

|

8M

|

291M

|

22M

|

20M

|

351M

|

6. Results of Online Questionnaire:

I. General Demographics

(1) Gender: Male, 79%; Female, 21%

(2) Age:

|

Under 16

|

18-24

|

25-30

|

31-35

|

36-40

|

41-50

|

51-60

|

Over 60

|

|

2.4%

|

42.8%

|

32.8%

|

10.2%

|

5.7%

|

4.5%

|

1.2%

|